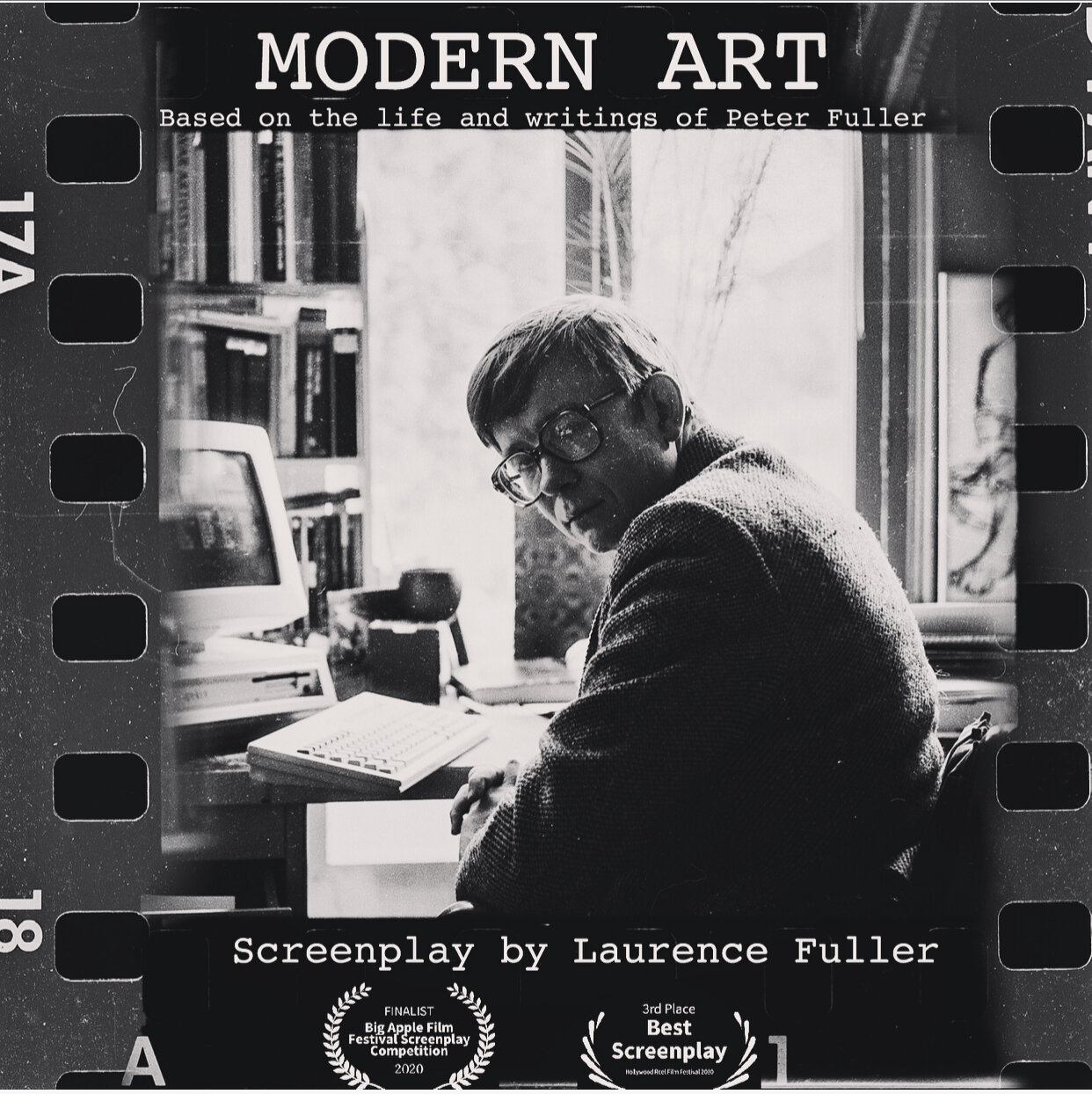

MODERN ART chronicles a life-long rivalry between two mavericks of the London art world instigated by the rebellious art critic Peter Fuller, as he cuts his path from the swinging sixties through the collapse of modern art in Thatcher-era Britain, escalating to a crescendo that reveals the purpose of beauty and the preciousness of life. This Award Winning screenplay was adapted from Peter’s writings by his son.In September 2020 MODERN ART won Best Adapted Screenplay at Burbank International Film Festival - an incredible honor to have Shane Black one of the most successful screenwriters of all time, present me with this award:

As well as Best Screenplay Award at Bristol Independent Film Festival - 1st Place at Page Turner Screenplay Awards: Adaptation and selected to participate in ScreenCraft Drama, Script Summit, and Scriptation Showcase. These new wins add to our list of 25 competition placements so far this year, with the majority being Finalist or higher. See the full list here: MODERN ART

HAYWARD ANNUAL 1979

by Peter Fuller, 1979

The Arts Council began to organize ‘Hayward Annuals’ in 1977: the series is intended to ‘present a cumulative picture of British art as it develops’. The selectors are changed annually. The Hayward Annual 1979 was really five separately chosen shows in one. It was the best of the annuals so far: it even contained a whispered promise.

Frank Auerbach portrait of James Hyman

I want to look back: the 1977 show was abysmal, the very nadir of British Late Modernism. The works shown were those of the exhausted painters of the 1960s and their epigones. Even at their zenith these artists could do no better than produce epiphenomena of economic affluence and US cultural hegemony. But to parade all this in the late 1970s was like dragging out the tattered props of last season’s carnival in a bleak mid-winter. The exhibition was not enhanced by the addition of a few more recent tacky conceptualists, although four of the exhibiting artists—Auerbach, Buckley, Hockney and Kitaj—each showed at least some interesting work.

The 1978 annual, selected by a group of women artists, was, if anything, even more inept. It was intended to ‘bring to the attention of the public the quality of the work of women artists in Britain in the context of a mixed show’. Some of Elizabeth Frink’s sculptures seemed to me to be good, though that was hardly a discovery. There was little else worth looking at.

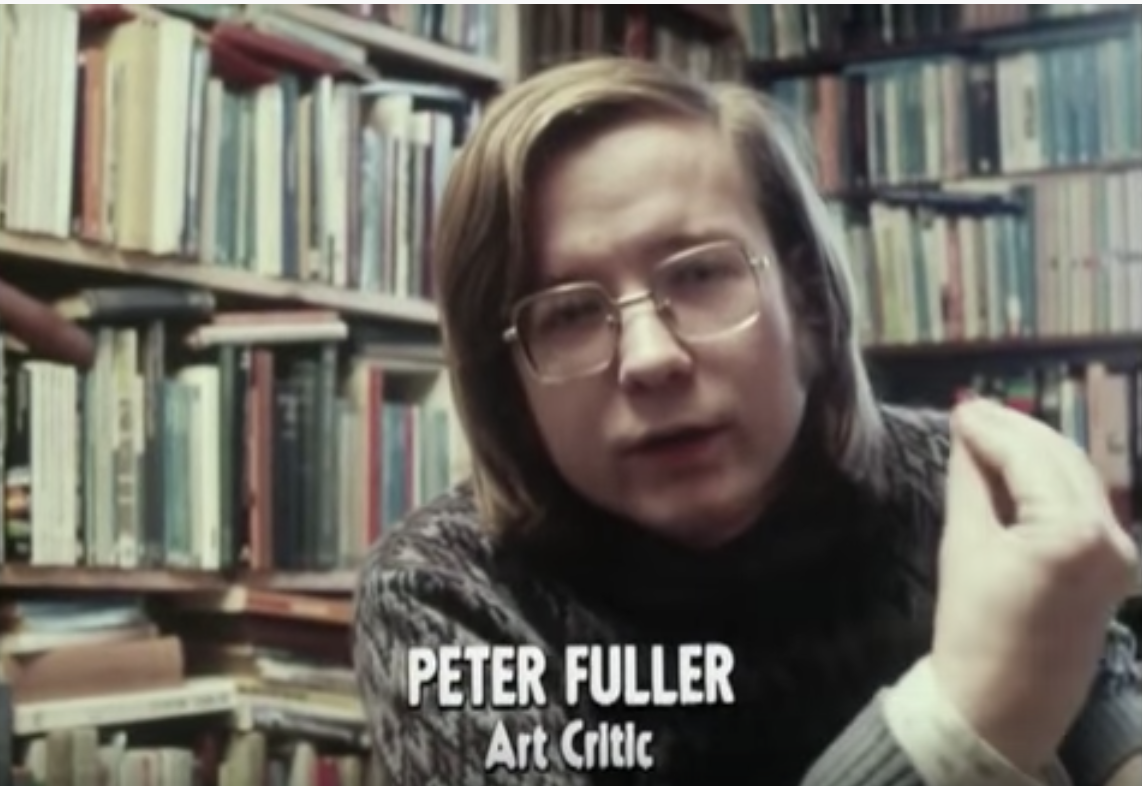

It was in the face of the transparent decadence of British art in the 1970s (clearly reflected in the first two annuals) that a vigorous critical sociology of art developed. Writers such as Andrew Brighton and myself were compelled by history to develop in this way given the absence (at least within the cultural ‘mainstream’) of much art which was more than a sociological phenomenon. We were forced to give priority to the question of where art had gone and to examine the history and professional structures of the Fine Art tradition. We attended to the mediations through which a work acquired value for its particular public. Andrew Brighton emphasized the continuance of submerged traditions of popular painting which persisted outside the institutions and discourse of modernism. I focused upon the kenosis, or self-emptying, which manifested itself within the Late Modernist tradition itself. Critical sociology of art was valuable and necessary: it has not yet been completed, and yet it was not, in itself, criticism of art.

The sonorous Protestant theologian, Karl Barth, used to draw a sharp distinction between ‘religion’ (of which he was contemptuous) and ‘revelation’, the alleged manifestation of divine transcendence within the world through the person of ‘The Christ’, by which he purported to be awed. Now I am a philosophical materialist. I have no truck with religious ideas: what I am about to write is a metaphor, and only a metaphor. However it seems to me that over the last decade it is as if we had focused upon the ‘religion’ of art—its institutions and its ideology—not because we were blind to ‘revelation’ but because it was absent (or more or less absent) at this moment in art’s history.

The problems of left criticism have, as it were, been too easily shelved for us by the process of history itself. During the decade of an ‘absent generation’ and the cultural degeneracy of the Fine Art tradition the question of quality could be evaded: one grey monochrome is rarely better or worse than another. Indeed, in the 1960s and 1970s, the debate about value became debased: we saw how the eye of an ‘arbitrary’ taste could become locked into the socket of the art market, and the art institutions there become blinded with ideology and self- interest, while yet purporting to swivel only in response to quality. But these are not good enough reasons for indefinitely shirking the question of value ourselves.

In his book, Ways of Seeing, John Berger distinguished between masterpieces and the tradition within which they arose. However, he has recently made this self-criticism: ‘the immense theoretical weakness of my own book is that I do not make clear what relation exists between what I call “the exception” (the genius) and the normative tradition. It is at this point that work needs to be done’. I agree, but this ‘theoretical weakness’ (which is not so much Berger’s as that of left criticism itself) runs deeper than an explanation of the relationship of ‘genius’ to tradition. Works of art are much more uneven than that: there are often ‘moments of genius’ imbedded with the most pedestrian and conventional of works. But at these points, the crucial points, talk of‘sociology of art’, ‘visual ideology’ or historical reductionism of any kind rarely helps.

I believe neither that the problem of aesthetics is soluble into that of ideology, nor that it is insoluble. Trotsky, thinking about the aesthetic pleasure which can be derived from reading the Divine Comedy, ‘a medieval Italian book’, explained this by ‘the fact that in class society, in spite of all its changeability, there are certain common features.’ The elaboration of a materialist theory of aesthetics for the territory of the visual is a major task for the left in the future: such a theory will have to include, indeed to emphasize, these ‘biological’ elements of experience which remain, effectively, ‘common features’ from one culture and from one class to another. In the meantime, I cannot use the absence or crudeness of such a theory as an excuse for denying that certain improbable works (with which, ‘ideologically’, I might be quite out of sympathy) are now beginning to appear in the British art scene which have the capacity to move me. When that begins to happen, it becomes necessary to respond as a critic again, and to offer the kinds of judgement which, since Leibnitz, have been recognized as being based upon a knowledge which is clear but not distinct, that is to say not rational, and not scientific.

Let me hasten to add that the 1979 Hayward Annual seemed to me no more than a confused and contradictory symptom. Nothing has yet been won. It was rather as if an autistic child whom one had been attending had at last lifted his head only to utter some fragmented and indecipherable half-syllable. But even such a gesture as that excites a hope and conveys a promise out of all proportion to its significance as realized achievement. The exhibition, which I am not inclined to reduce entirely to sociology, was an exhibition where some works, at least, seemed to be breaking out of their informing ‘visual ideologies’. An exhibition where, perhaps, those ‘moments of becoming’ which I have been ridiculed for speaking of before may have been seen to be coming into being.

The five loosely labelled component categories of the exhibition are ‘painting from life’, ‘abstract painting’, ‘formal sculpture’, ‘artists using photographs’ and ‘mixed media events’. I want to deal briefly with each.

‘Painting from life’ consists of the work of six artists chosen by one of them (Paul Chowdhury). Now it is easy to be critical of the style which dominates this section. Chowdhury’s selection looks like an attempt to revive an ebbing current of English painting on the crest of the present swell towards ‘realism’, i.e. in this instance, pedantic naturalism. Most of these artists have links with the Slade’s tradition of ‘objective’ empiricism and particularly with that peculiarly obsessive manifestation of it embodied in the art and pedagogy of Sir William Coldstream. This tendency has its roots deep in the vicissitudes of the British national conjuncture, and in the peculiar complexion of the British ruling-class. Here I do not wish to engage in an analysis of the style: despite their affinities, these paintings are not a homogenous mass. Indeed the section is so uneven that one can only suspect that Chowdhury (who is certainly in the better half) sometimes allowed mere stylistic camaraderie to cloud his judgement.

Let me first clear the ground of that work which fails. At forty-seven, Euan Uglow is on his way to becoming an elder statesman of the continuing Slade tradition. This is hard to understand. His paintings here are much more frigidly formalist than anything to be seen in the adjacent ‘abstract painting’ room. In works like The Diagonal, Uglow decathects and depersonalizes the figures whom he paints. To a greater extent even than Pearlstein he degrades them by using them as excuses for compositional exercises. He is so divorced from his feelings that he has not yet proved able to exhibit a good painting. Uglow, at least, has the exactitude of a skilled mortician. By contrast, Norman Norris is a silly and sentimental artist who uses the trademarks of measured Slade drawing as decorative devices. In a catalogue statement he writes that he hopes to discover a better way of coping with the problem his drawing method has left him with. ‘For this to happen’, he adds, ‘my whole approach will have to change’. This, at least, is true. In the meantime, it would be far better if he was spared the embarrassment of further public exposure.

Patrick Symons studied with the Euston Road painters; he is the oldest painter in this section, and his optic is also the most resolutely conservative. But, despite its extreme conventionality, his painting is remarkable for the amateurish fussiness and uncertainty it exhibits even after all these years. A painting like Cellist Practising is all askew in its space: walls fail to meet, they float into each other and collide. Certain objects appear weightless. Such things cannot just be dismissed as incompetence: Symons is nothing if not a professional. I suspect that the distortions and lacunae within his work are themselves symptoms of the unease which he feels about his apparently complacent yet historically anachronistic mode of being- within and representing the world. Symons’ bizarre spatial disjunctures mean that he is to this tradition what a frankly psychotic artist like Richard Dadd was to Victorian academic art.

Leon Kossoff

So much for the curios. There is really little comparison between them and work of the stature of Leon Kossoff’s: Kossoff is, as I have argued elsewhere, perhaps the finest of post Second World War British painters. He springs out of a specific conjuncture—that of post-war expressionism and a Bomberg-derived variant of English empiricism—a conjuncture which enabled him partially to resolve, or at least to evade, those contradictions which destroyed Jackson Pollock as both a man and a painter. (I have no doubt that Kossoff will prove a far more durable painter than Pollock.) But Kossoff transcended the conjuncture which formed him: his work never degenerated into mannerism. Outside Kilburn Underground for Rosalind, Indian Summer is, in my view, one of the best British paintings of this decade.

As for Volley and Chowdhury themselves, they are the youngest artists in this section: their work intrigues me. In Chowdhury, the lack of confidence in Slade epistemology is not just a repressed symptom. It openly becomes the subject matter of the paintings: if we do not represent the other in this way, Chowdhury implies, how are we to represent him or her at all? He exhibits eight striking images of the same model, Mimi. His vision is one in which, like Munch’s, the figure seems forever about to unlock and unleash itself and to permeate the whole picture space. (Chowdhury has realized how outline can be a prison of conventionality.) In his work subjectivity is visibly acknowledged: it flows like an intruder into the Slade tradition where it threatens (though it never succeeds) to swamp the measured empirical method. The only point of fixity, the only constant in these ‘variations on a theme’ is the repeated triangle of the woman’s sex. Both in affective tone and in their rigorous frontality these paintings reminded me of Rothko’s ‘absent presences’—though Chowdhury is not yet as good a painter as Rothko. In Chowdhury the fleshly presence of the figure is palpable, but its very solidity is of a kind which—particularly in Mimi Against a White Wall—seems to struggle against dissolution.

Volley is a ‘painterly’ painter: he is at the opposite extreme from Uglow. In his work the threat of loss is perhaps even more urgent than in Chowdhury’s. Over and over again, Volley paints himself, faceless and insubstantial, reflected in a mirror in his white studio. Looking at his paintings I was reminded of how Berger once compared Pollock to ‘a man brought up from birth in a white cell so that he has never seen anything except the growth of his own body’, a man who, despite his talent, ‘in desperation . . . made his theme the impossibility of finding a theme’. Volley, too, knows that cell, but the empirical residue to which he clings redeems him from utter solipsism. He is potentially a good painter.

The ‘abstract painters’ in this exhibition were chosen by James Faure Walker who also opted to exhibit his own work: again, the five painters chosen have much in common stylistically, though the range of levels is almost equally varied. These are all artists who have been, in some way or another, associated with the magazine A rtscribe, of which Faure Walker is editor. A rtscribe emerged some three years ago as a shabby art and satire magazine. It benefited from the mismanagement and bad editing of Studio International, once the leading British modern art journal, which has been progressively destroyed since the departure of Peter Townsend in 1975. (There have been no issues since November 1978.) Around issue seven, Art scribe mortgaged its soul to a leading London art dealer, which precipitated it into a premature and ill- deserved prominence.

Artscribe claimed that it was written by artists, for artists: it was, in fact, written by some artists for some other artists, often the same as those who wrote it, or were written about in it. Unfortunately, the regular Artscribe writers have been consistent only in their slovenliness and muddledness; the magazine has never come to terms with the decadence of the decade. It has, by and large, contented itself with cheery exhortations to painters and sculptors to ‘play up, play up and play the game’.

Despite denials to the contrary its stance has been consistently formalist. Recently, Ben Jones, an editor of Artscribe, organized an exhibition—revealingly called ‘Style in the 70s’—which he felt to be ‘confined to painting and sculpture that was uncompromisingly abstract—the vehicle for pure plastic expression both in intention and execution.’ Much of the critical writing in Artscribe has shown a meandering obsession with the mere contingencies of art, a narcissistic preoccupation with style and conventional gymnastics. This has been combined with an almost overweening ambition on the part of the editors to package and sell the work of themselves and their friends, the art of the generation that never was, the painters who were inculcated with the dogmas of Late Modernism when Late Modernism itself had dried up. Indeed, there are times when Artscribe reads like something produced by a group of English public school-boys who are upset because, after trying so hard and doing so well, they have not been awarded their house colours. It is noticeable that all the ‘ragging’ and pellet flicking of the first issues has gone: now readers are beleaguered with anal-straining responsibility, and upper sixth moralizing . . . but Artscribe has yet to notice that there are no more modernist colours. The school itself has tumbled to the ground.

Now this might be felt to be a wretched milieu within which to work and paint, and by and large, I suspect it is. ‘Style in the 70s’ is, as one might expect, a display of visual ideology. Oh yes, most of the artists are trying to break a few school rules, to arrest reductionism, to re-insert a touch of illusion here, to threaten ‘the integrity of the picture surface’ there—but most of it is style, ‘maximal not minimal’: its eye is on just one more room in the Tate. But—and this is important—it is necessarily style which refuses the old art-historicist momentum: there was no further reduction which could be perpetrated. The very uncertainty of its direction has ruptured the linear progress of modernism: within the resulting disjuncture, some artists— not many, but some—are looking for value in the relationship to experience rather than to what David Sweet, a leading Artscribe ideologist, once called ‘a plenary ideology developed inside the object tradition of Western Art’.

Take the five artists in the Hayward show; again, it is easy enough to clear the ground. Bill Henderson and Bruce Russell are mere opportunists, slick operators who are slipping back a bit of indeterminate illusionism into pedantic, dull formalist paintings. Faure Walker himself is certainly better than that. His paintings are pretty enough. He works with a confetti of coloured gestures seemingly dragged by some aesthetic- electric static force flat against the undersurface of an imaginary glass picture plane. The range of colours he is capable of articulating is disconcertingly narrow, and his adjustments of hue are often wooden and mechanical—as if he was working from a chart rather than allowing his eye to respond to his emotions. Nonetheless the results are vaguely— very vaguely—reminiscent of lily pools, Monet, roseate landscapes, Guston and autumnal evenings. Faure Walker is without the raucous inauthenticity of either a Russell or a Henderson.

The remaining two painters in this group—Jennifer Durrant and Gary Wragg—are much better. They are not formalists: just compare their work with Uglow’s, for example, to establish that. I do not get the feeling that, in their work, they are stylistic opportunists or tacticians. They have no truck with the punkish brashness of those who want to be acclaimed as the new trendies in abstraction. In fact, I do not see their work as being abstract in any but the most literal sense at all: they are concerned with producing powerful works which can speak vividly of lived experience.

Wragg’s large, crowded paintings present the viewer with a shifting swell of lines, marks, and patches of colour: his works are illusive and allusive. Looking, you become entangled in them and drawn through a wide range of affects in a single painting. ‘Step by step, stage by stage, I like the image of the expression—a sea of feeling’, he wrote in the catalogue. He seems to be going back to Abstract Expressionism not to pillage the style—though one is sometimes aware of echoes of De Kooning’s figures, ‘dislimned and indistinct as water is in water’—so much as in an attempt to find a way of expressing his feelings, hopes, fears and experiences through painting. His work is still often chaotic and disjunctured: he still has to find himself in that sea. But Morningnight of 1978 is almost a fully achieved painting. His energy and his commitment are not to contingencies of style, but to the real possibilities of painting. He is potentially a good artist.

The look of Durrant’s work is quite different. Her paintings are immediately decorative. They hark back—sometimes a little too fashionably—to Matisse. A formalist critic recently wrote of her work, that it has ‘no truck with pseudo-symbolism or half baked mysticism. The only magic involved comes from what is happening up front on the canvas, from what you see. There is nothing hidden or veiled, nor any allusions that you need to know about’. If that were true, then the paintings would be nothing but decoration, i.e. pleasures for the eye. I am certain, however, that these paintings are redolent with affective symbols—not just in their evocative iconography, but, more significantly, through all the paradoxes of exclusion, and engulfment with which their spatial organizations present us. Now there is an indulgent looseness about some of her works: she must become stricter with herself; paintings like Surprise Lake Painting, February-March 1979 seem weak and unresolved. However, I think that already in her best work she is a good painter: she is raising again the problem of a particular usage of the decorative, where it is employed as something which transcends itself to speak of other orders of experience —a usage which some thought had been left for dead on Rothko’s studio floor, with the artist himself.

Durrant and Wragg manifest a necessary openness. Like Chowdhury and Volley, they are conservative in the sense that they revive or preserve certain traditional conventions of painting. But they are all prepared to put them together in new ways in order to speak clearly of something beyond painting itself. Levi-Strauss once explained how the limitation of the bricoleur—who uses bits and pieces, remnants and fragments that come to hand—is that he can never transcend the constitutive set from which the elements he is using originally came. All these artists are, of necessity, bricoleurs: Levi Strauss has been shown to be wrong before, and I hope they will prove him so again.

Something similar is also happening in the best British sculpture: you can see it most clearly at the Hayward in Katherine Gili where the debased conventions of welded steel have taken on board a new (or rather an old) voluminousness, and seem to be struggling towards expressiveness: imagery is flooding back. Such work seems on the threshold of a real encounter with subject matter once more. Quite a new kind of figuration may yet burst out from this improbable source.

The other two sections in the Hayward Annual, ‘artists using photographs’ and ‘mixed media events’ seemed to me irrelevant to that flickering, that possible awakening within the Fine Art tradition. The ‘mixed media events’ were a waste of time and space. The fact that a pitiful pornographer like P. Orridge continues to receive patronage and exposure for his activities merely demonstrates the degree to which questions of value and quality which I began by raising have been travestied and betrayed during this decade by those in art institutions who have invoked them most frequently.

There is just a chance that we may be coming out of a long night. Immediately after the last war some artists—most notably Leon Kossoff and Frank Auerbach—produced powerful paintings in which they forced the ailing conventions of the medium in such a way that they endeavoured to speak meaningfully of their experience; as a result, they produced good works. Some younger artists—just a few—now seem to be going back to that point again, and endeavouring to set out from there once more. They cannot, of course, evade the problem of the historic crisis of the medium. Whether they will be able to make the decisive leap from subjective to historical vision also yet remains to be seen.

But if what one is now just beginning to see does indeed develop then, with a profound sense of relief, I will shift further away from ‘sociology of art’ (which is what work like P. Orridge demands, if it demands anything more than indifference) towards the experience offered by particular works, and the general problems of aesthetics which such experiences raise. I hope that I will not be alone on the left in doing so. The desire to displace the work by an account of the work (which I have never shared) can only have any legitimacy when the work itself is so debased and degenerate that there is no residue left within it strong enough to work upon the viewer or critic, when, in short, it is incapable of producing an aesthetic effect.

1979