Maggi Hambling has an exhibition at Marlborough Gallery in London until October 24th. Maggi was one of my father's favorite artists around the time of his death, he believed she was one of England's best contemporary painters and the proceeding 27 years have only further proved that to be the case.

In research for the film I'm developing about my father, the late art critic Peter Fuller, I've been going through archival footage of his documentaries and TV appearances, I found this clip of him talking about her painting The Minotaur.

Maggi Hambling’s obituary for Peter Fuller:

Peter Fuller and Maggie Hambling c. 1990

"At supper a couple of weeks ago Stephanie Fuller told me I was one of Peter's 'things'. A daunting description. If Peter believed in your work, his commitment was total and passionate. This was completely un-English, extremely rare, and therefore disconcerting. But of course Peter liked to disconcert. His courage was real because it was equalled by his 'voolnerability', as he always, deliberately, pronounced the word. I only got to know him properly last October when we went to New York to look at Velasquez. I am indebted to him for seeing 'Picasso and Braque' the following day, which opened my eyes to Cubism. We argued; we laughed. His capacity to laugh at himself was one of his greatest charms. Your last request to me, Peter, was to put in writing for this magazine my amazement at your claim in your last Editorial that it was unacceptable to love the smell of both shit and roses'. This struck me as uncharacteristically ungenerous of you. I would say that shit (along with Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock) has its rightful place in life's rich pattern, Peter. How can you deny the rose's sensual pleasure as it experiences fresh cow-dung, horse manure and at moments the surprising products of our own animal bodies? Unworthy of you, my friend. But I shan't hold it against you, just as you never held other people's ideas against them. The Dickensian feasts with Peter and Stephanie of the last two New Year's Eves in Suffolk remain loud in my ears, ingrained in my liver and warm in my heart. It is your passion and your humour that I miss most, Peter, and I delighted in being one of your 'things'." - Maggi Hambling

MAGGI HAMBLING

By Peter Fuller

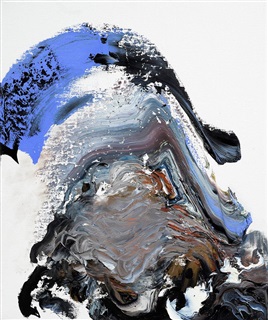

Minotaur Surprised while Eating, Maggi Hambling 1986-87

In Minotaur Surprised while Eating of 1986-7 the beast, half-man, half-animal, is shown devouring a joint of human flesh, morsels of which hang down from his bovine jaw. He glances out at us with a look of apprehension in his piercing eyes, which seem as human as his hands. This painting was among the most shocking and the most outstanding in Maggi Hambling's pictures of people, animals, landscapes, mythological and religious subjects shown at the Serpentine Gallery in 1987. Hambling has long displayed exemplary skill as a draughtswoman, but this body of pictures confirmed her as an artist of great imaginative depths and unexpected stature.

Hambling was born in Sudbury, Gainsborough's home-town, in 1945, and spent her childhood in Hadleigh, in Constable country. Her Head of Christ (1986) now hangs in Hadleigh church. While still at school, she took her paintings to the nearby 'Artists' House', home of Cedric Morris and Lett Haines. Soon she became one of their pupils. Haines, in particular, taught her to have confidence in her own imagination. Later, she continued her studies at Camberwell, under Robert Medley, and, for a short time in the 1960s, her figures resembled his fractured forms. Although Medley's stylistic influences were later much less apparent, he - like Haines - exerted a more general effect on her development as an artist.

Hambling went to the Slade School in 1967, where she reacted against the rich British imaginative and empirical traditions which had, in various ways, played their part in her early development. A confused period of environmental and conceptual work followed, but it was inevitable that an artist possessed of such considerable gifts would soon return to drawing and painting. In 1972, she began to paint people. Her portrait heads of this time were reminiscent of those early pictures by David Hockney which contain traces of child art, combined with Francis Bacon's savage viewpoint.

Hambling moved towards a more personal vision when she focused on one sitter, Frances Rose, an elderly neighbour. The Frances Rose pictures began to address themselves to one of the central concerns of Hambling's maturity: the search for a way of painting 'fallen' modern men and women without resorting to the monstrous, but reaching beyond the limits of empiricism. Her paintings of the mid-1970s revealed a sympathy with human frailty and impoverishment, but they did not always escape a certain murkiness of colour and handling, as if the content was constraining the form. Her more visionary sentiments split off into fantasy and mythical subjects like the Garden of Eden, now at Petworth House.

A deepening and a broadening of Hambling's vision occurred in 1977, after she visited Madrid to study Goya. Her British roots were nourished by her sense of her place within a wider European culture. This was confirmed by the time she spent as the National Gallery's first 'Artist-in-Residence', in 1980-1. Her best-known works of this period were the series of paintings and drawings she made of the comedian, Max Wall, exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in 1983. The Max Wall paintings combined a sense of the mundane - of the absurdity, sadness and vulnerability of human life - with vivid images of the transforming power of reverie, wit, illusion and imagination, suggested by the magical wreaths and wisps of cigarette smoke, like something from a genie's lamp, that appear again and again in these pictures. It was as if Frances Rose had strayed into paradise garden! And yet, despite the poignancy of these works, even the best of them seemed infected with a note of sentimentality. This was apparent as much in drawing and gestures (which sometimes veered towards caricature) as in the subject - the old, smoking clown whose heart bleeds.

The paintings Hambling produced in the four years leading up to the Serpentine exhibition show a more confident fusion of imaginative and empirical elements than anything she had previously achieved. Some of her pictures of people, such as Untitled (1986), hark back to earlier modes. This harrowing work shows a tramp lying prostrate among the rubbish in the street. The awkward handling of the figure offers no glimpse of anything beyond the dreadful mortality revealed to us.

Sunrise, Maggi Hambling 1990

With Hambling's Sunrises, matters are different. These works stem from a small painting she made in Suffolk in 1984. For a long time the work hung at the bottom of her bed before she decided to make a much bigger version of it. This proved to be the first of a series of pictures of sunrises, painted with a brilliance, at times even a stridency, quite new in her work. They show the moment when, quite literally, night shrivels, and the living darkness is subsumed by light and colour.

A series of bull-fight paintings form the inverse of the sunrises - in both mood and form. In pictures like Fallen bull (1985), Dead bull (1987), or Fifth bull, the often bizarre location of the brute, black mass of the dead or dying creature threatens to swallow up all the colour and life around it. This repeated ritual of death becomes a pictorial 'negative' of the diurnal resurrection of the dawn.

It is not my wish to imply that Maggi Hambling is an artist of the stature of Bacon or of Rothko, and yet the union of natural and formal symbolism in these sunrise and bull-fight pictures suggests that she is looking for ways beyond the limitations of distorted physicalism or engulfing vacuity. Her most achieved pictures indicate that she is finding some sort of aesthetic solution in the replenishment of mythical painting. Minotaur Surprised while Eating and Pasiphae and the Bull (1987) are paintings of an exemplary strength which etch themselves immediately and indelibly into the imagination of the viewer. The poignancy of the pictures derives from Hambling's improbable union of the closest, and most obsessive, observation of bull and human bodies with higher aspirations. The monstrous creatures and acts depicted associate the carnal appetites of men and women with the brutishness of the beasts, red in hoof and claw.

In Minotaur Surprised while Eating, 1986-7, the Minotaur turns his eyes on us with an alert and guilty look, as if we b'd interrupted him in the middle of his bloody meal. This terrible image is set against an almost abstract background of mingling green and gold, in which the sky and ground seem to merge.

The Minotaur, Watts

When I first saw this picture in Hambling's studio, I was reminded of a little-known picture by George Frederick Watts, the Victorian painter of mythic and allegorical subjects. Admittedly, there are many differences between the two works. Watts placed his Minotaur on the edge of a battlement, made him the predator not of huge joints of human flesh, but of a single tiny bird, and turned his monstrous features, discreetly, away from the viewer. Nonetheless, the two pictures have much in common; not least the abstracted background against which the bull-man is set. For Watts's Minotaur has been made to gaze out across the vast and enticing emptiness of an infinite sea.

Hambling had not seen Watts's picture before she painted hers, and yet the resemblances between these two works may be more than mere analogy. For one thing, they are both interpretations of the same Greek myth. According to the legend, the Minotaur came into being because Poseidon, the God of the Sea, caused Pasiphae, the wife of Minos, to become enamoured of a great bull which had been held back from sacrifice. Pasiphae told Daedalus, an exiled Athenian craftsman, about her strange passion, and Daedalus made a fake cow for her constructed out of hide, cast over a wooden frame on wheels.

This contraption was placed in the meadow where the great bull grazed, and Pasiphae slid inside it, with her legs splayed out inside its make-shift hindquarters. The bull was deceived, and mounted her, and so she had her pleasure. Hambling has depicted their union in a shocking picture, Pasiphae and the Bull, 1987. This, of course, is not a subject Watts would have attempted, and, even if he had, he would not have dispensed with the cowhide to bare Pasiphae's white and fragile flanks to our gaze, or contrived to place the bull's enormous black member as the very pivot of his picture.

The Minotaur was the monstrous progeny of this union. Minos gave orders that every ninth year seven young men and seven maidens should be sacrificed to the flesh-eating creature. The victims were released into the maze of the Labyrinth where the Minotaur waited to ensnare and devour them. And this is what we see him doing in Maggi Hambling's Minotaur. In Watts's version he is looking out for the boat from Athens which will come bearing fresh victims.

Whatever the Minotaur may have meant to the Greeks, he seemed to have a horrible poignancy for the Victorians. If nature had once appeared beneficent, almost a garden made by God for man, it was quite suddenly transformed, in the nineteenth century, into something savage and threatening. Charles Kingsley complained that he could no longer see spiritual truths or moral order in a natural world in which everything was always eating everything else. Simultaneously, belief in the Christ, or the incarnate God-man, who sacrificed himself to save man from sin, became increasingly difficult to sustain. Watts saw that the predatory, life-destroying bull-man was a more compelling symbol of modern man's selfconception, which was re-shaping itself more in the image of the brutes than of God.

If today there seems something a little comic - a touch, perhaps, of Bottom and A Midsummer Night's Dream - about Watts's Minotaur, it is perhaps because he reveals so vividly the aesthetic dilemmas which followed upon the heels of the Victorians' spiritual crisis. Watts's Minotaur gazes, forlornly, at a quivering, blue void - as if he and all his monstrous peers were about to become engulfed and subsumed by it. (Remember, 'A most rare vision ... It shall be called Bottom's dream because it hath no bottom'?)

Aleppo II, Maggie Hambling, 2016

In a sense he was being engulfed, for many in the emergent Modern movement believed that abstraction was the only means by which the vistas of spiritual truth might be opened up in painting, now that they could no longer be glimpsed through the features of men, animals, plants or landscapes. I like to think that if Maggi Hambling's Minotaur faces the other way, it is because he stands on the farther shore of the Modern movement. His back has been turned upon abstraction which can no longer provide a credible escape from our fallen condition in a seemingly godless world.

The Sleep of Reason Begets Monsters, Francisco Goya 1798

In one sense, Hambling confronts us with our brutish nature in a more relentless way than Watts would ever have dared. We sense that Goya must have been an important influence upon her. But if she repudiates the seductive blankness of the abstraction which lies behind the night-creatures in Goya's famous print, The Sleep of Reason Begets Monsters, she also struggles to offer something more than fallen 'realism'.

For a painter like Francis Bacon, the Victorian nightmare becomes reality. His evil genius depicts men and women as indistinguishable from the teeth, claws and raw sexual convulsions of the brutes and carnivores. Although Hambling's work is resolutely secular, she seems intuitively to want to find hints and traces of, if not redemption, then at least a kind of reconciliation. She does not deny our animal nature, but still finds hints of the great promises which religion once offered. This sense of transfiguration can be found in such things as the pathos in the faces of her clowns, the glory of the Suffolk sunrises, and even in the magnificent, sacrificial fall of her bulls.

Look again at the expression in the eyes of her Minotaur. Certainly, there is evil here. But is that all? The creature's gaze reminds me of something John Keats wrote in one of his letters: 'The greater part of Men make their way with the same instinctiveness, the same unwandering eye from their purposes, the same animal eagerness as the Hawk. The Hawk wants a mate, and so does the man - look at them both, they set about and procure one in the same manner. I go among the fields and catch a glimpse of a stoat or a field mouse peeping out of the withered grass - the creature hath a purpose and its eyes are bright with it.'

We never see this glint of intention in, say, Bacon's monstrously pulverised faces. Despite all his malevolent grandeur, Bacon has been so overcome by the problem of evil that he loses all sight of purpose and intention. Hambling finds them again, even in the midst of evil itself. In Hambling's mythological works, the luminous and aureate backgrounds of burning gold verge on the numinous mists of abstraction, and yet also recall the redemptive splendours of the dawn paintings. Like Keats, she seems to be seeking a route which leads beyond Kingsley's dilemma, a route between the Scylla of Bacon's monstrous realism and the Charybdis of Rothko's abstract sea of silence.

Not surprisingly, one of her most remarkable paintings to date, Christ in Venice (1987), consists of a dramatic reinterpretation of a scene from the Passion. The sombre black and purple background recalls the void of Rothko's wine-dark seas, but the raised-up body of Christ suggests the harrowing and uneasy hedonism of later Titian, whom Hambling had been studying in Venice before she painted this picture. The frail body of Jesus rises above the grimacing crowd which bears him towards his death and reminds us of the fallen world of the modern grotesque - that caricatured and ignoble 'realism', through which, as unbelievers, we have hitherto seemed compelled to confront ourselves.

We might say that everything depicted is all too human, but it is not less than that. Hambling's painting offers hints if not of salvation, in any miraculous or other-worldly sense, at least of ethical and spiritual hope. With a growing confidence, she is finding original plastic and iconographic forms appropriate to this vision. Little wonder, then, that she has looked again into the eyes of the Minotaur.

1987