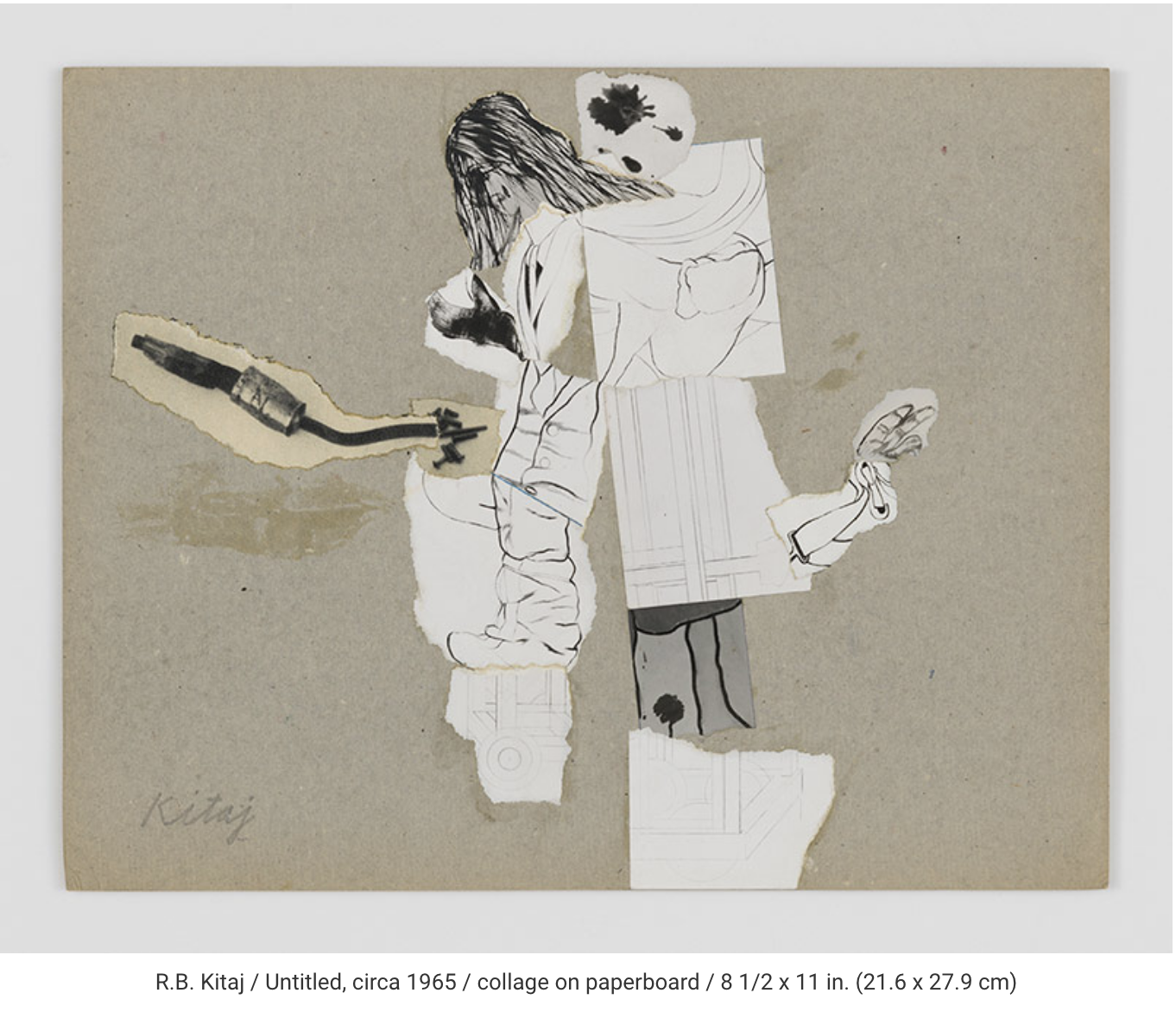

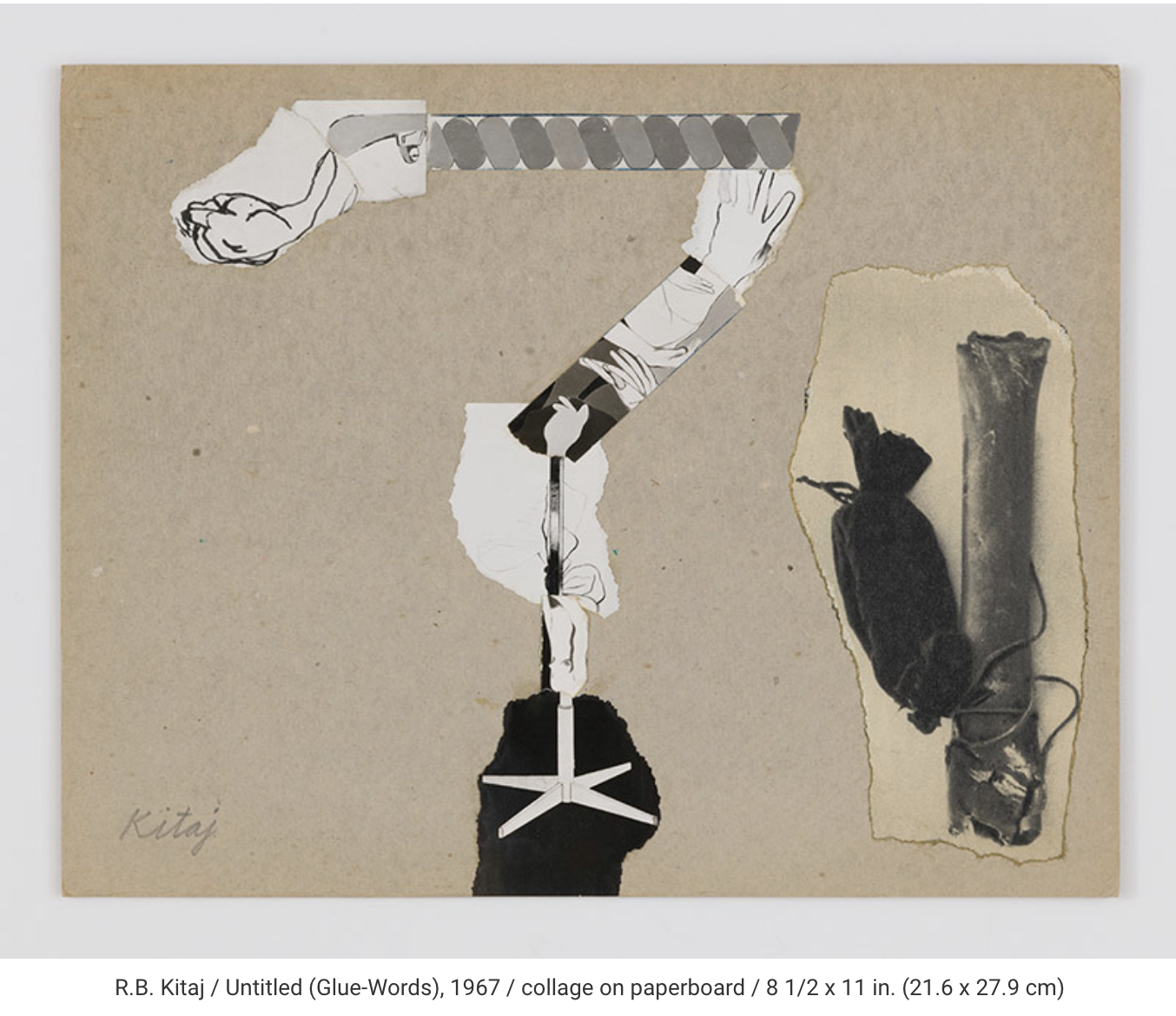

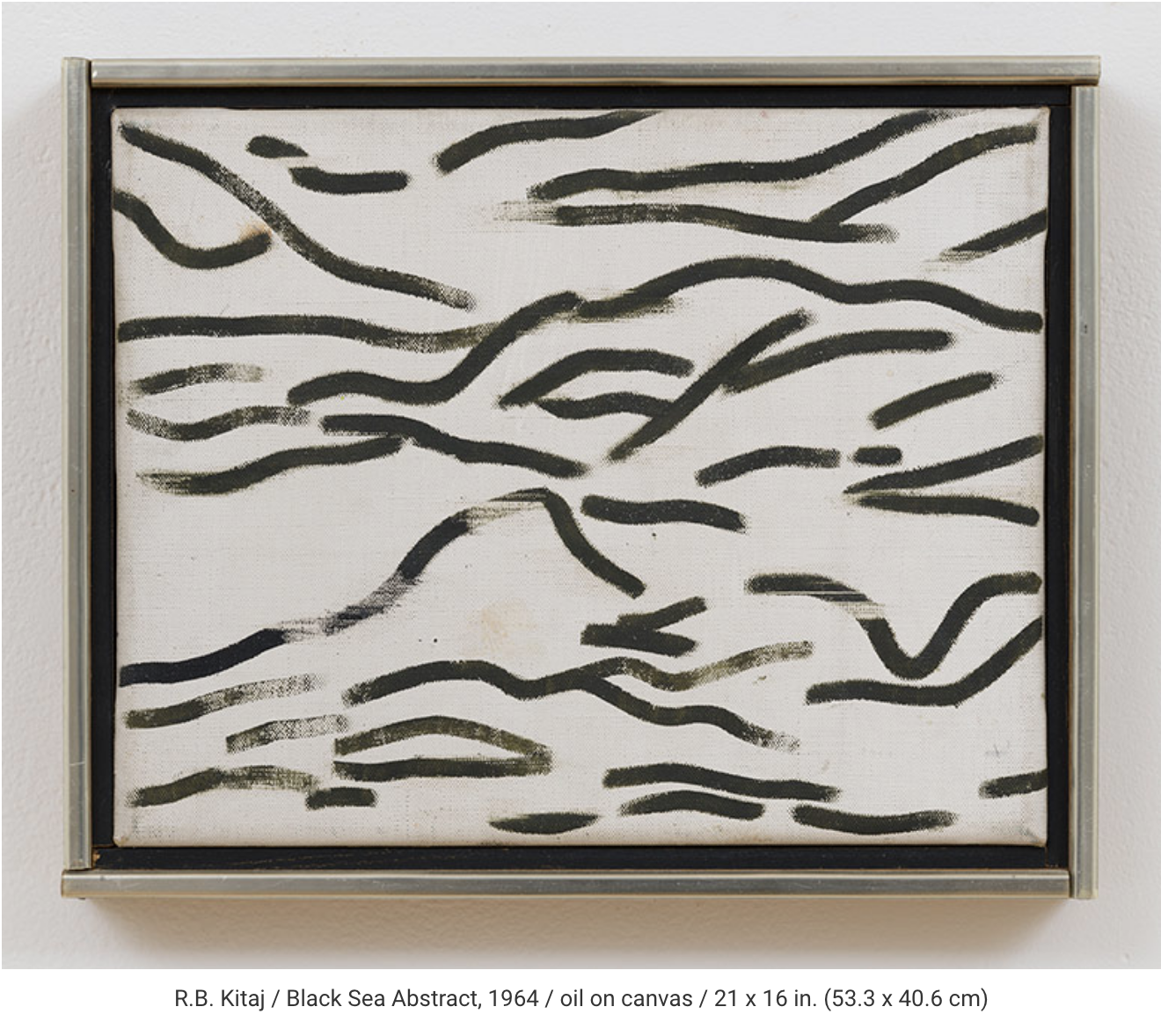

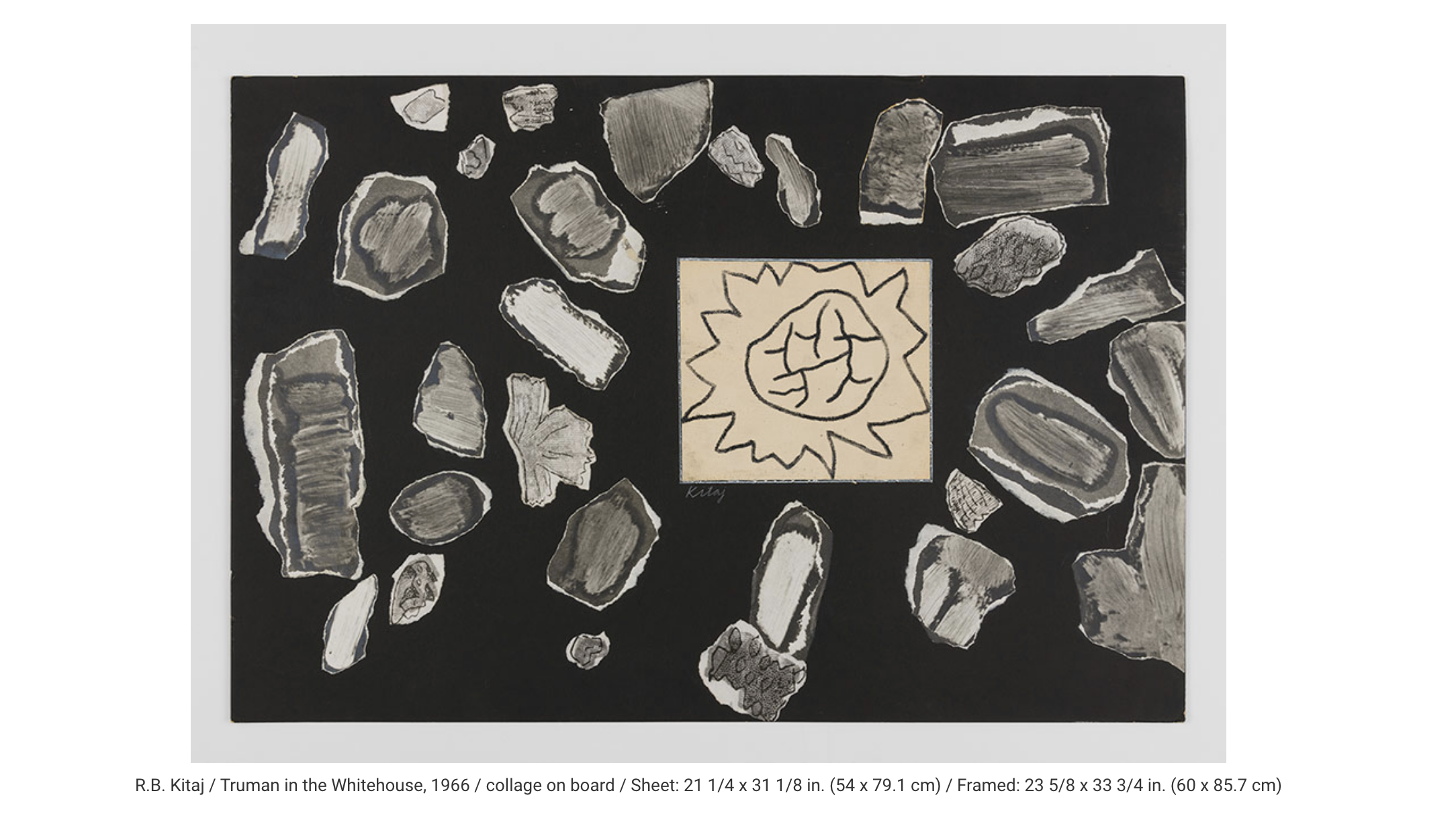

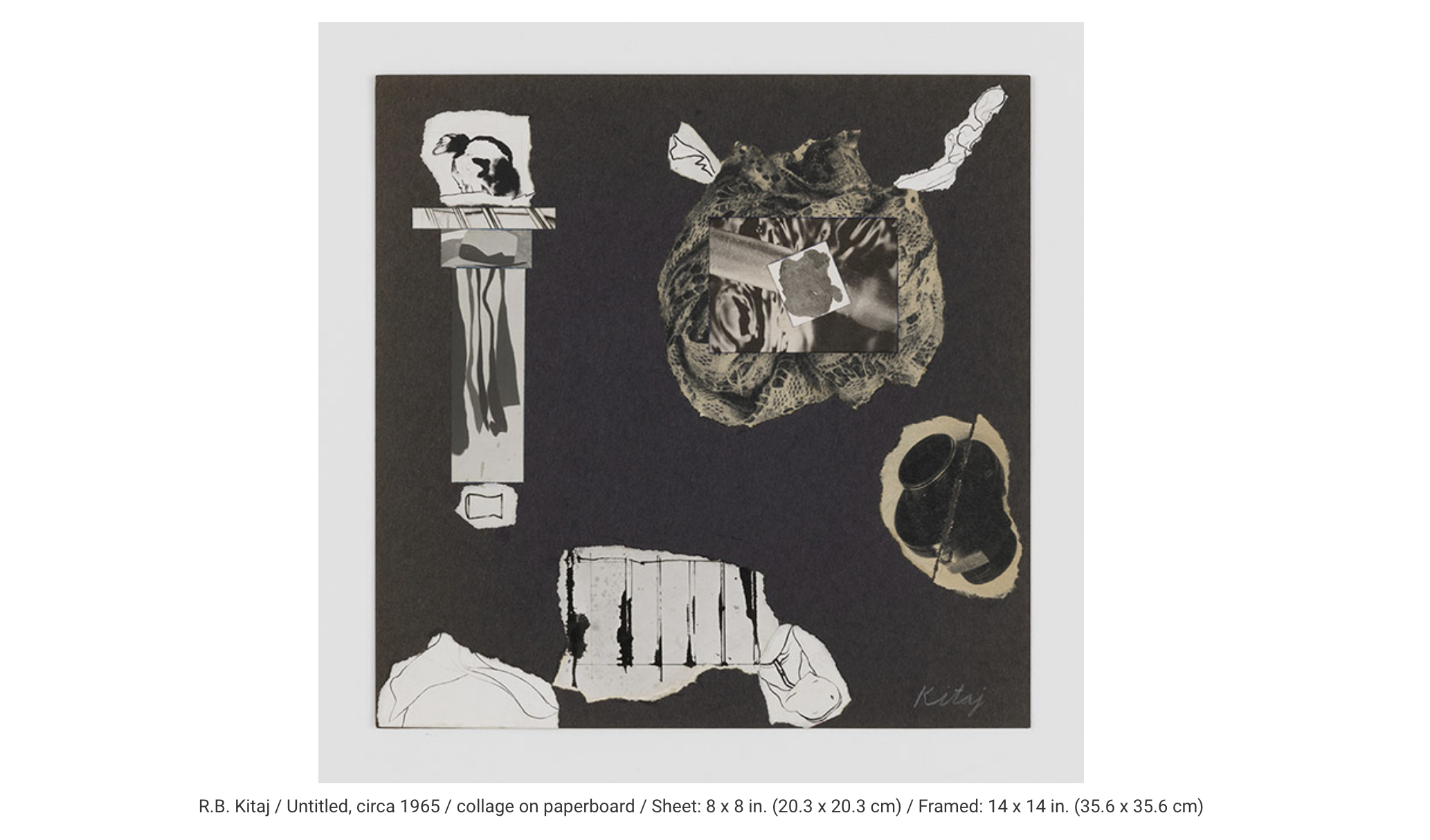

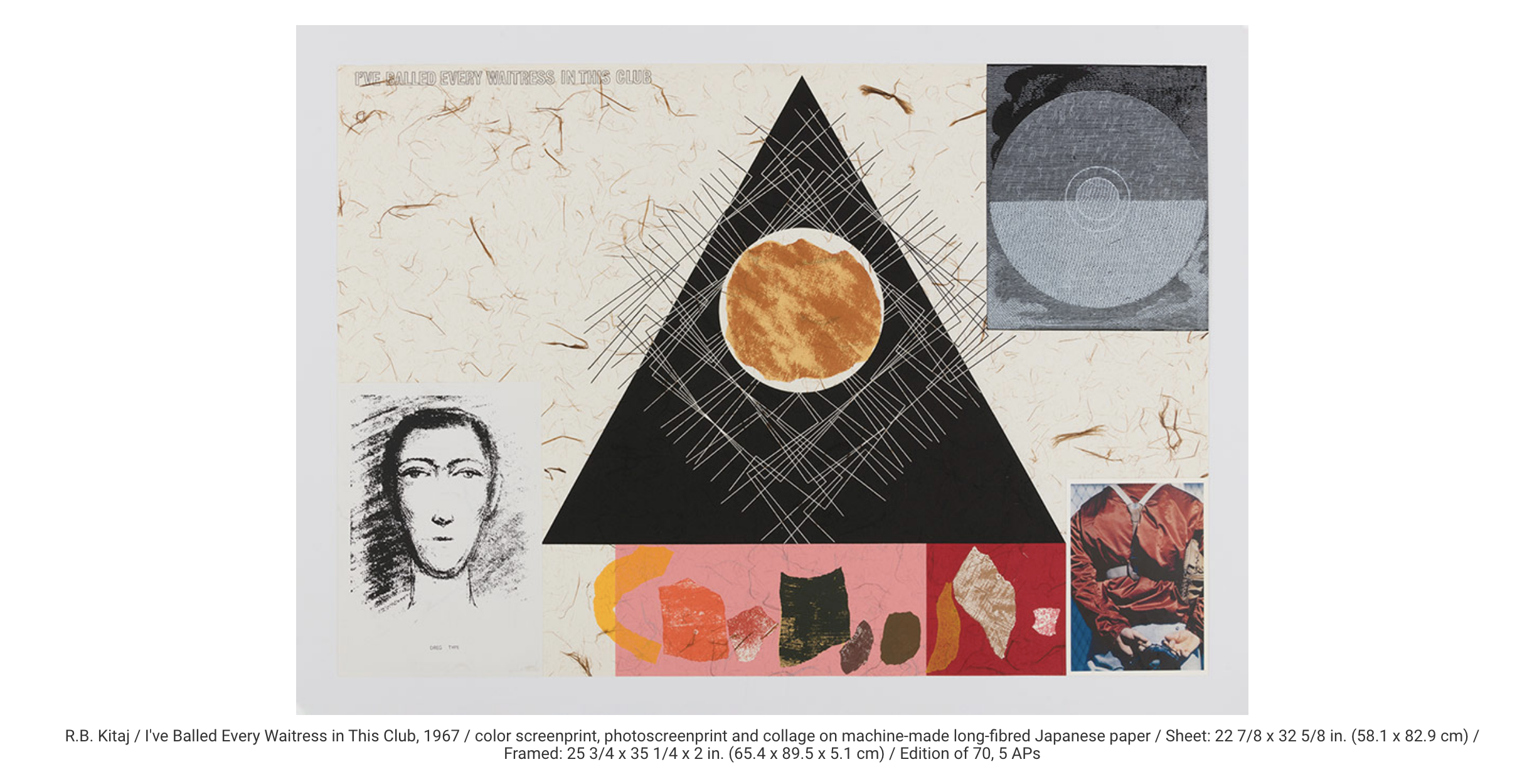

LA Louvre is hosting an exhibition of R.B. Kitaj’s collages and prints, 1964-1975, in Venica CA, until January 18th, 2020.

To accompany the event I’m posting below Peter Fuller’s article on Kitaj, initially published in Modern Painters, 1986.

To read more on the Peter Fuller project click the image >

R.B. KITAJ

by Peter Fuller

In the catalogue to his 1985 exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery, Ron Kitaj wrote, 'Art “about" Jews does not appear much among painters, although a new "German" art has appeared with a bang, has it not?' Kitaj's recent paintings are a self-conscious attempt to redress this balance - to make art which is explicitly and unashamedly about Jews.

Kitaj confesses to being haunted by memories of the holocaust, and fears for the future. 'That epochal murder,' he writes, 'happened during my youth, and now, after the greatest trouble they were ever in, Jews find themselves in peril again.' Kitaj argues he could not proceed as a painter without a heightened sense of Jewishness. In a lecture he gave recently in Oxford, he explained that in him, the Jewish spirit was 'a long time in the forming and coming'. He told his audience it began to stir seriously about five years ago, 'although chimerical aspects of Jewishness had tempered my life and art for many years'. He recalled, 'One third of our people were being murdered while I was playing baseball and going to movies and high school and dreaming of being an artist.'

Nowhere are all these concerns more evident than in a painting called Germania (The Tunnel), of 1985. In a self-portrait on the left-hand side of the painting Kitaj depicts himself wearing a vest and trousers splattered with blood and black arrows. He carries a stick because he is lame. One of his legs is caught in a chimney-like structure - a repeated iconographic device which runs through many of these works. In front of the painter is a boy child who has just learned to walk. He is bearing a book and pointing towards the printed page. Kitaj never allows us to forget that Jews are 'People of the Book'.

In the right foreground is a naked woman, seen from the back. She too appears ensnared within an evil chimney shape. Behind these figures stretches a long, arched corridor which has been borrowed in every detail from a Van Gogh painting of the Saint-Remy asylum where he was incarcerated. This corridor immediately evokes the gas-chambers, and culminates in a small golden door. Kitaj recalls that the inscription 'Paradise Alley' hung above the entrance to one of the chambers of death in Auschwitz.

About a year ago, Kitaj's son, Max, was born. The theme of this painting then might be said to be, 'How do I, an artist and a Jew, bring up my son to know about things like the holocaust?' Minutes after Kitaj had told me this, in his gallery on the morning of the day on which his exhibition opened, I watched Max stand and take his first faltering unaided steps only a few yards away from Germania (The Tunnel).

Another of the paintings in this exhibition was called, Self- Portrait as a Woman. This shows a naked, female figure, again seen from the back, and apparently wearing a placard. Kitaj lifted this image from holocaust literature which told how, during the Third Reich, certain women were taken and paraded naked in public with a sign round their necks saying, 'I slept with a Jew'. Kitaj identifies himself, as an artist and a Jew, with such a woman. S/He is transformed in his painting into a kind of hero/ine. Once again, the structure of the figure and placard suggests the recurrent symbol of the death-camp chimney. This is echoed in the church tower in the background, for Kitaj has set the lurid scene against the back-drop of a beautiful, almost magical, small German town. This contrast is reminiscent of the way in which certain 'Primitive' and early Renaissance paintings depict the Crucifixion as a glorious event which took place in front of a magnificent, fairy-tale city.

Many of these themes are also reflected in what is, perhaps, the finest single picture in the exhibition, The Jewish Rider, of 1984-5. The painting is a portrait of Michael Podro, the art historian, who is shown seated and reading - a text always enters in somewhere - in a railway carriage. The chimney is again conspicuous, this time in the corridor on the right-hand side of the painting which is occupied by a menacing uniformed figure who raises a lash high in the air. Through the window on the left-hand side of the picture, one sees a bruised but beautiful wasteland, in the midst of which a single tall chimney smokes. Kitaj has long been fascinated by a newspaper report which related that the trains of death on their way to Auschwitz passed through an extraordinarily beautiful landscape.

In the painting called Yiddish Hamlet (Y. Loivy), 1985, Kitaj depicts Lowy, a member of a lowly group of Yiddish travelling players. Lowy was a friend of Kafka's who lived a despised life. 'A Man of Sorrows', rejected of men, he died at Auschwitz. Kitaj depicts him encased within that cylindrical chimney structure.

The assertion of Jewishness, and the struggle for symbols adequate to that assertion, have become the central preoccupation of Kitaj's painting. These pictures have already proved something of a scandal and a stumbling-block. Other Jews, especially other Jewish painters, recoil with embarrassment. (Kitaj points out that there is much more coherent 'Jewish spirit' among writers than among visual artists. No one hesitates to call Philip Roth - of whom Kitaj has made some fine drawings -a Jewish writer; but Auerbach, Freud or Kossoff are never referred to as Jewish painters.) Gentiles, on looking at these pictures, are likely to feel a sense of exclusion at the expression of emotions with which they can sympathise but not empathise.

Conventional wisdom has long been that the Jewish experience in the Third Reich was so extreme and horrific that no painting could ever encompass it. Ironically, one of the few attempts to deal directly with the death camps in painting is a Crucifixion by Graham Sutherland which now hangs in St Matthew's Church, Northampton. Sutherland explained that the whole idea of the depiction of Christ crucified became much more real to him after having seen a book containing 'the most terrible photographs of Belsen, Auschwitz and Buchenwald'. For the first time, 'it seemed to be possible to do this subject again'.

For Kitaj, a Jew rather than a convert to Roman Catholicism, the treatment of Jewish experience required a symbol other than that of the Christian Cross. He admits, however, that it was the Christian Passion of Rouault which inspired him to embark on his Jewish Passion. 'I made a startling discovery,' he writes. 'There seem to be no representation of the Crucifixion itself in art for hundreds of years after the event.'

Peter Lasko suggested to him that the earliest known one may be on the wooden doors of Santa Sabina in Rome, which date from the fifth century. But Kitaj insists the subject was not a familiar one for hundreds of years after that. 'Anyway,' he adds, 'I thought - why wait 400 years after our (Jewish) Passion?' The appearance of his chimney form is, he suggests, 'my own very primitive attempt at an equivalent symbol, like the Cross, both, after all, having contained the human remains in death'.

But it seems to me that there are many queries and objections we ought to raise before we can accept this parallel, for the idea that the image of the Cross was expunged from the early history of Christianity will not stand up. Representations of the Cross (if not the Crucifixion) pervaded Christian culture long before the fifth century, let alone the eighth century.

In the second century, Justin the Martyr perceived the Cross everywhere, even where it was not. According to Justin, Plato believed that the Logos, the power next to God, 'was placed crosswise in the universe'. Justin also saw numerous 'types' of prefigurements of the ubiquitous Cross in classical literature. Homer describes how Odysseus asked his shipmates to lash him to the mast of his boat so he could hear the allurements of the Sirens and survive. Justin interprets the episode as a foreshadowing of the way in which the death of Jesus on the Cross enabled men and women to conquer sin and death.

Where the Cross could not be seen the early Christians readily re-created it for themselves. 'At every forward step and movement,' writes Tertullian, 'at every going in and out... in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we mark upon our foreheads the sign.' According to Eusebius, when the Emperor Constantine was converted to Christianity, he saw the trophy of a Cross of light in the heavens above the sun, bearing the inscription: 'CONQUER BY THIS' (Touto nika). Lactantius tells us that Constantine was directed in a dream to cause the heavenly sign to be delineated on the shields of his soldiers, before proceeding to battle and to victory.

The Emperor's mother, Saint Helena, was believed to have found the true Cross in Jerusalem, allegedly establishing its authenticity by using it to raise the dead. Constantine himself forbade the continued use of crucifixion as a method of capital punishment because the Cross had now become a royal banner, or talisman - a symbol of 'Christ the King'. The Emperor Julian the Apostate forsook Christianity. 'You adore the wood of the Cross,' he complained of his fourth-century Christian subjects, 'and draw its likeness on your foreheads and engrave it on your house fronts.'

No one then can say that the Cross was an unfamiliar element in early Christian culture. As Augustine so vividly put it, 'The deformity of Christ forms you. If he had not willed to be deformed, you would not have recovered the form which you had lost. Therefore he was deformed when he hung on the Cross. But his deformity is our comeliness. In this life, therefore, let us hold fast to the deformed Christ.'

Why then, are there so few representations of the deformed Christ surviving from the early centuries of Christian faith? One simple reason, which Kitaj seems to ignore, is the fervour of the iconoclastic movements of the eighth century. So ferocious and fanatical were the image-breakers that it is more wondrous that any early Christian representations have come down to us, rather than so few. But this is not the only reason. We also have to take account of the process of 'elevation' of the Cross. That is, the way in which the sordid reality of a particular Roman execution became transmuted into a sign of magical power and of conquest.

That crucifixion was at first not even a speck in the tide of imperial history. The 'holocaust' of Roman crucifixion has been overlooked, as hundreds of thousands of men and women were crucified by the Romans, who used the cross as an instrument of terror, as well as of punishment. There were times when the arenas of the Empire bristled with crosses. After the defeat of the Spartacus uprising in 71 BC, almost 6,500 crosses lined the Appian Way from Capua to Rome. About their passion, the church is silent.

Kitaj also seems to be missing another seminal fact about the Crucifixion of Jesus. The Christian tradition subjected itself from the time of Paul onwards to a process of dejudification. Although the Jews were often accused of the 'Murder of Christ', little mention was made of the fact that Jesus was not a Christian but a Jew. He was, in fact, a Jewish prophet, who saw himself not as Messiah, but rather as playing some part in the imminent apocalyptic processes which could bring about the literal establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth - a Kingdom in which the Jews, as children of God, would be restored to their rightful place in the world order. Instead, the proclaimer became the proclaimed and the instrument of his absolute defeat and humiliation was elevated as the emblem of his divine, all-conquering power.

Kitaj, then, is right when he implies that Christianity found itself when it created the effective symbol for its passion, the Cross. He is wrong, however, to regard this as an unproblematic achievement - as one which Jewish art and culture should seek to emulate. For this process of the elevation of the Cross was one of the ways in which the Jewishness of Jesus (and therefore of Christian culture as a whole) was obscured, clearing the way for the persecution of the Jews and the holocaust itself.

Those who think this is an exaggeration should read the excellent book by Jaroslav Pelikan, Jesus Through the Centuries. Pelikan, an historian who believes that theology is too important to be left to theologians, points out that one twentieth-century artist, at least, clearly perceived Jesus as, first and foremost, a Jew, rabbi and prophet. That artist was himself a Jew: Marc Chagall.

In his White Crucifixion, Chagall depicts Jesus as wearing not a nondescript loincloth but the tallith of a devout and practising rabbi. The pivot of this painting is a prophecy attributed to Jesus by John: They will put you out of the synagogues; indeed the hour is coming when whoever kills you will think he is offering service to God.' Chagall has seen this as having been fulfilled, in a supreme irony, when some who claimed to be disciples of Jesus regarded the persecution of Jews as a service to God. We should not allow ourselves to forget that, during the Third Reich, some Christian theologians elaborated the idea of 'Christ the Fiihrer', the Leader or Ruler, and effectively identified the German Fiihrer, with his swastika and intense hostility to Jews, with Jesus. Though the swastika dates back to the pre-Christian era, the Nazis recognised that it provided a parody, or approximation, for the triumphant Cross of Christ, as the very name, Hakenkreuz, implies.

'Would there have been such anti-Semitism,' asks Pelikan, 'would there have been so many pogroms, would there have been an Auschwitz, if every Christian church and every Christian home had focused its devotion on icons of Mary not only as Mother of God and Queen of Heaven but as the Jewish maiden and the new Miriam, and on icons of Christ not only as Pantocrator but as Rabbi Jeshua bar-Joseph, Rabbi Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of David, in the context of the history of a suffering humanity?'

I must confess my admiration for Kitaj's audacity, for his courage and ambition as a painter, and above all for the dazzling strength of his line, which seems to draw so much of its power from that of Degas - who, we should not forget, stood firmly on the wrong side in the Dreyfus Affair. Nonetheless, I believe that Kitaj was closer to a symbolism capable of expressing these themes when he was less self-consciously obsessed with the idea of replacing the emblematic cross with the emblematic chimney; when his iconography was at once more particular and more universal.

If Not, Not - R.B. Kitaj

When Marco Livingstone's monograph on Kitaj first fell into my hands, I turned eagerly to the series of 'Prefaces' to particular paintings by Kitaj himself which are published as an appendix to the book. I wanted to find out what Kitaj had to say about If Not, Not, of 1975-6 - a picture which I first saw in Timothy Hyman's Narrative Painting exhibition of 1979 [see plate 20a]. In a lecture called, 'Where was the art of the seventies?', delivered in 1980 said that If Not, Not was one of the very best paintings of the last decade. That is a view from which I have never wavered - although I had never been able to unravel much of the picture's complex iconography.

What I read surprised me - for Kitaj relates this canvas, too, to what Winston Churchill called 'the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the whole history of the world'. He informs us that the great architectural structure which dominates the upper left-hand corner of the canvas is the Auschwitz gatehouse. In the journal he kept for the painting he first made notes about that train journey which a journalist took from Budapest to Auschwitz to get a sense of what the doomed could see through the slats of their cattle cars. As I have said, the fact that it was 'beautiful countryside' affected him deeply.

Kitaj also reveals that the references threaded through If Not, Not are literary and symbolic, as well as historical. The painting, he says, is permeated by 'a certain allegiance to Eliot's Waste Land and its (largely unexplained) family of loose assemblage'. Eliot, like Degas, was not uninfected with an unsavoury anti- Semitism, but Kitaj wanted to echo one particular eddy within the poem - the theme of the Waste Land as 'an antechamber to Hell'. He draws attention to the fact that there are passages in Eliot's masterpiece where drowning, 'Death by Water', is associated with the death of someone close to the poet - perhaps a Jew.

Now I have to admit that though I must have looked at my reproduction of the picture admiringly hundreds of times over a period of several years, much of this simply passed me by. I had picked up that 'certain allegiance' to Eliot and even briefly wondered - wrongly, as Livingstone now tells me - whether the figure at the bottom left, wearing a hearing-aid and looking back through spectacles at a naked woman, was not meant to be a likeness of the poet who not only wrote The Waste Land, but had a lot of trouble with his women and his sexual drives. I even picked up a general likeness, which Kitaj acknowledges, to Giorgione's Tempesta; and responded to an image of a polluted and degraded paradise, the pool of which was 'stagnant in the shadow of a horror'. But I had never thought of If Not, Not as a Jewish holocaust painting.

Here was a particular symbol, which achieved the universal because it relinquished none of its particularity. The Auschwitz gatehouse was, indeed, the gateway to Hell, and this image of a soiled Eden - a promised land flowing with blood and bandages - reached me, a Gentile, touched me, and moved me deeply.

Gentile or Jew

O you who turn the wheel and look to windward,

Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

Something of this has gone in Kitaj's most recent paintings. The generalised chimneys are no longer representations of the gatehouse to Hell, but rather items of iconography. 'Maybe it's best not to paint about such things as Crucifixions and Passions in art,' Kitaj himself asks, 'because one is bound to fail?' But Pelikan comments on Chagall's rabbinical Jesus, 'the central figure does indeed belong to the people of Israel, but he belongs no less to the church and to the whole world - precisely because he belongs to the people of Israel'.

If Not, Not also seemed to me to approach the universal through an unremitting insistence upon the particular. But, ironically, Kitaj's more recent affirmation of his Jewishness through his painting seems to me to be painting conventional loincloths over forgotten talliths. The irony may be that these paintings do not 'belong to the whole world' because they do not belong, sufficiently, 'to the people of Israel'. Not even Kitaj's chimneys can redeem him from the dilemma with which he has wrestled throughout his life. Those of us who lack faith must live without a guiding symbolic order. We inhabit the Wasteland. Like Phlebas, we are damned, Gentile or Jew.

1986