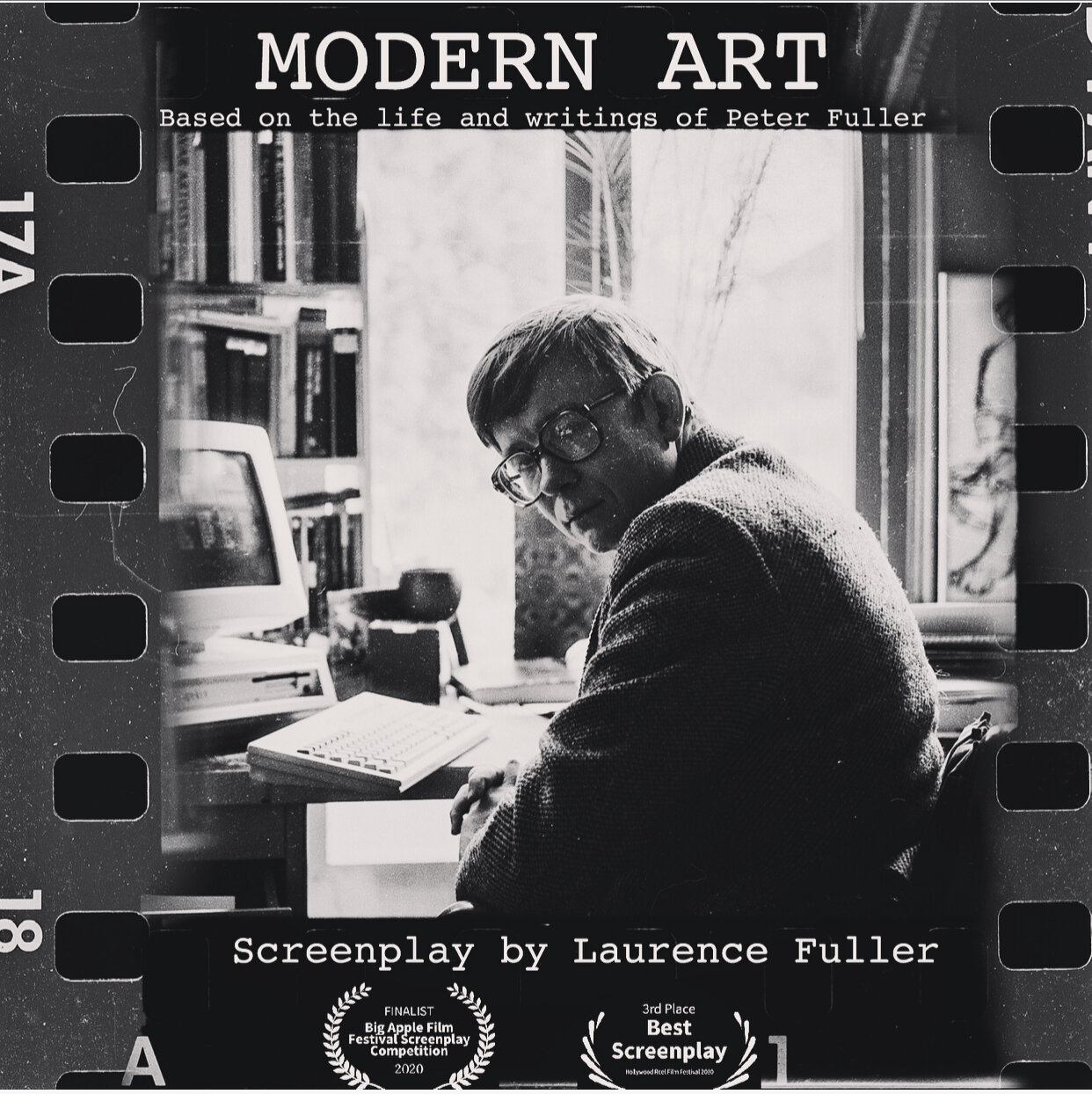

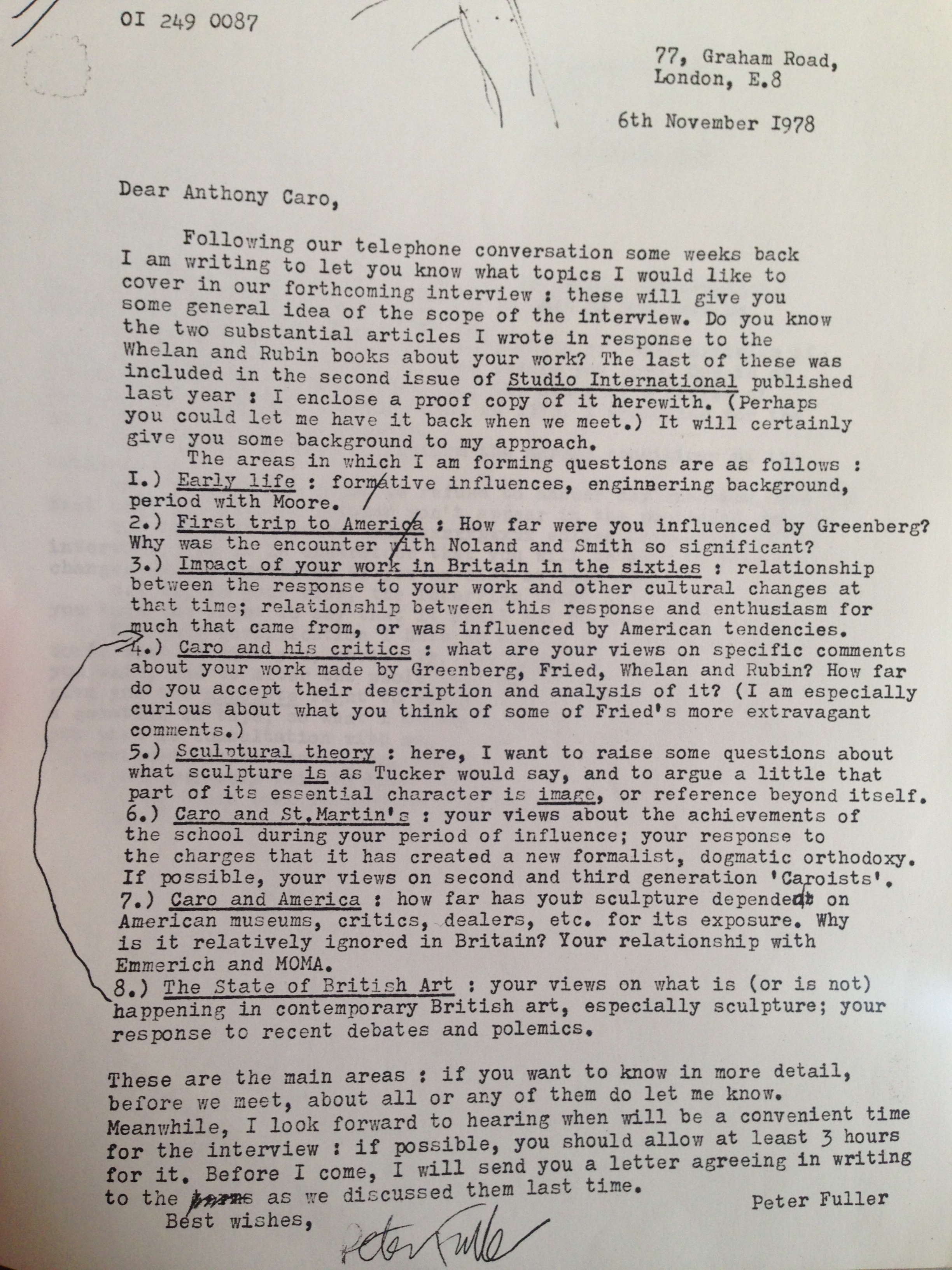

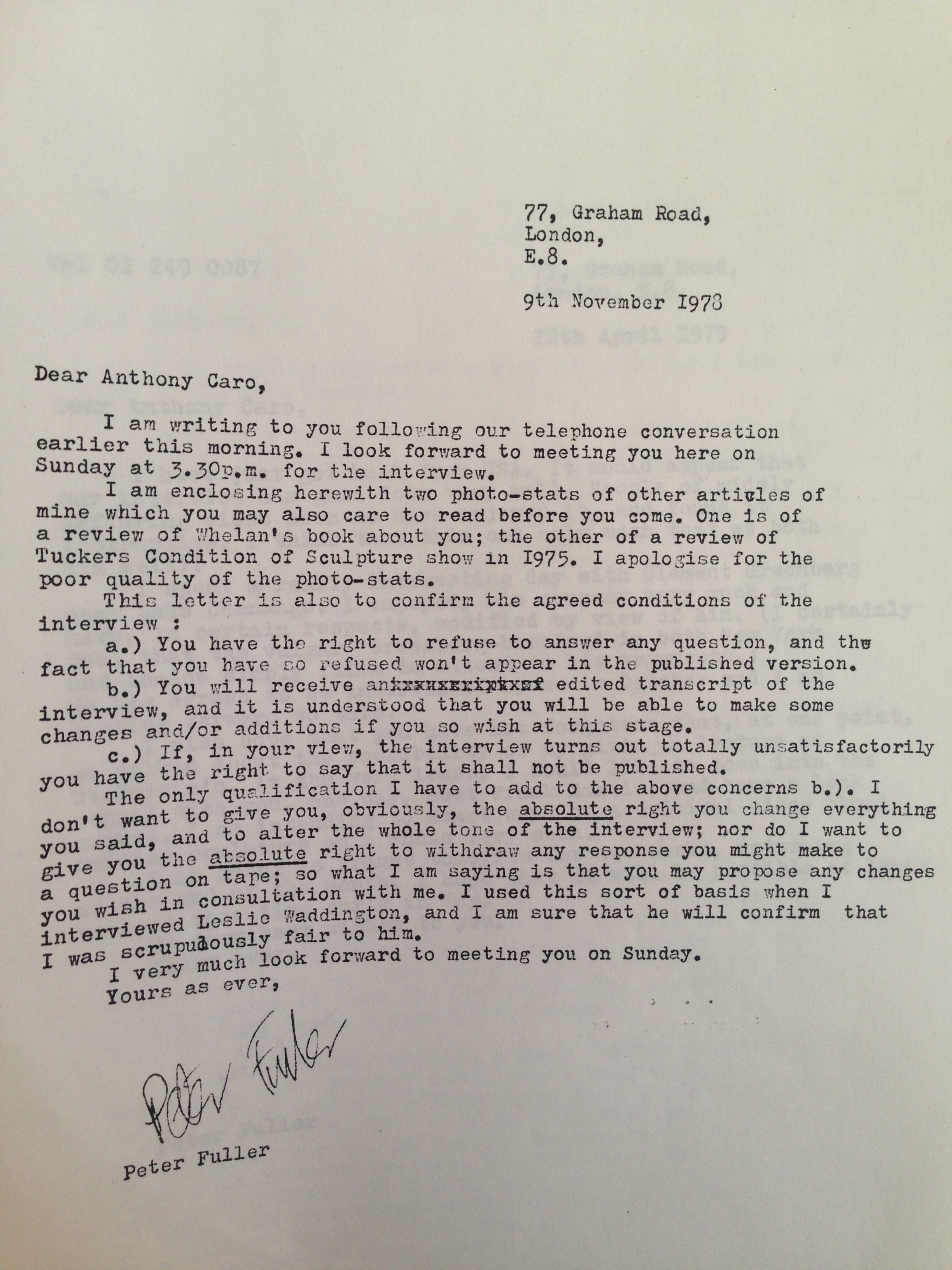

As well as Best Screenplay Award at Bristol Independent Film Festival - 1st Place at Page Turner Screenplay Awards: Adaptation and selected to participate in ScreenCraft Drama, Script Summit, and Scriptation Showcase. These new wins add to our list of 25 competition placements so far this year, with the majority being Finalist or higher. See the full list here: MODERN ART

The arts across the world are under attack right now, the telling comments by the likes of Rishi Sunak that artists should ‘re-train’, clearly show the administration’s priorities when it comes to supporting the arts at this time. i know that my father would have had a great deal to say about this. So you can read selected essays by Peter Fuller here on my blog during down time! I will be posting regularly.

Questions of Taste

by Peter Fuller, 1983

Design likes to present itself as clean-cut, rational and efficient. Taste, however, is always awkward and elusive; it springs out of the vagaries of sensuous response and seems to lose itself in nebulous vapours of value. Questions of taste have thus tended to be regarded by designers as no more than messy intrusions into the rational resolution of ‘design problems’. Alternatively, others have attempted to eradicate the issue altogether by reducing ‘good taste’ to the efficient functioning of mechanisms.

But taste has conspicuously refused to allow itself to be stamped out - in either sense of that phrase. As the premises of the modern movement have been called into question, so taste has been protruding its awkward tongue again. For many of us, it is becoming more and more evident that pure ‘Functionalism’ is, and indeed always has been, a myth; taste enters deeply even into design decisions which purport to have eliminated it. But, more fundamentally, it is now, at least, beginning to be asked whether good taste and mechanism are in fact compatible, i.e. whether the Modernist ethic did not build into itself some fundamental thwarting or distorting of the potentialities of human taste.

A recent exhibition at the Boilerhouse, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, reflected both the revival of interest in questions of taste, and the confusion among designers concerning them. Stephen Bayley’s exhibition, called simply ‘Taste’, chronicled the history of the concept through ‘The Antique Ideal’; the impact of mechanisation in the nineteenth century and the reaction against it; ‘The Romance of the Machine’; contemporary pluralism; and the growing ‘Cult of Kitsch’ - or bad taste which acknowledges itself as such.

But Minale Tattersfield, who designed the exhibition, opted to exhibit those items which had gained approval in their own time on reproduction classical plinths, and those which had not on inverted dustbins. An exhibition which attempted to tell us that ‘Taste’ was a neglected issue of importance was thus, itself, in the worst possible taste. I believe this contradiction reflects a deep- rooted contemporary ambivalence about the nature and value of the concept of ‘Taste’, an ambivalence which is nowhere more manifest than in Stephen Bayley’s muddled commentary.

In the introduction to the little book produced to accompany the exhibition, Bayley committed himself to the view that taste is ‘really just another word for choice, whether that choice is to discriminate between flavours in the mouth or objects before the eye’. Thus Bayley claimed that taste did not have anything to do with values, beyond questions of personal whim. He claimed there really can be no such thing as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ taste: ‘These adjectives were added more than a hundred years after the concept was defined by people seeking to give the process of selection particular moral values which would help them justify a style which satisfied their image of themselves... or condemn one which affronted it.’ So, Bayley claimed, ‘Taste derives its force from data that is (sic) a part of culture rather than pure science.’ Taste, he argued, should be separated out from design ‘so that in future each can be better understood’.

Just a few pages later on, however, Bayley took a different tack. Unexpectedly, he began to argue there was a transcultural and transhistorical consensus about those qualities of an object which led to good design. (These he itemised as intelligibility in form; an appropriate choice of materials to the function; and an intelligent equation between construction and purpose, so that the available technology is exploited to the full.) Bayley then went on to say that those ‘principles of design’ were in fact ‘the Rules of Taste’. In an interview, he once said his own taste was ‘just Le Corbusier, really’: and his universals turn out to be suspiciously close to the sort of thing Le Corbusier might have said about his own style, though they would appear to eliminate numerous works in other styles.

And so, in effect, there are two Stephen Bayleys: one who believes that the issue of taste is as unimportant, and as unresolv- able, as individual whim or fancy; and the other, who, like every good Modernist, wants to assimilate taste to the inhuman authority of the machine. This confusion about taste in the heart and mind of the Director of the Boilerhouse project is at least fashionable in that it is symptomatic of a confusion which prevails among the ‘cultured’ urban middle-classes at large. With the weakening of Modernist dogmatism - at least outside the bunker of the Boilerhouse - it is the tendency to trivialise taste, however, which is uppermost. Again and again aesthetic taste is reduced to the lowest level of consumer preference; almost always, it is assumed to be a mere sense preference and usually the paradigm is taste in food. Such attitudes are inevitably commonly associated with the cult of Kitsch.

For example, among the extracts reproduced in Bayley’s book is one from an American writer, John Pile, who wrote an influential article, ‘In Praise of Tasteless Products’. Taste, according to Pile, means, ‘simply “preference” - what one likes or dislikes’. He notes that taste is the name of one of the five senses which lead ‘one person to prefer chocolate and another to prefer strawberry’. The very concept, he claims, ‘suggests an element of arbitrariness or even a lack of sense, that is, irrationality’. Taste, Pile concludes, ‘is a somewhat superficial matter, subject to alteration on a rather casual basis’.

Similarly, for John Blake, Deputy Director of the British Design Council, ‘the notion that qualitative judgements can be made about a person’s taste makes little sense if the word is used correctly.’ In an article entitled ‘Don’t Forget that Bad Taste is Popular’, Blake defends that pariah of all ‘good design’: the electric fire, embellished with imitation coal. For Blake, the designer has no right to reject such things if the market indicates that people want them. ‘A person’s taste’, writes Blake, ‘is characteristic of the person, like his height, the shape of his nose or the colour of his hair.’ He adds, ‘I have a taste for Golden Delicious apples, but my son prefers Cox’s. Does that mean that my taste is therefore superior to his, or vice versa?’

As we shall see, perhaps it does. But, for the moment, let us leave on one side the fact that in matters of taste it would be advisable to trust neither an American (who comes from an anaesthetized culture) nor someone who prefers Golden Delicious apples to Cox’s. My argument runs deeper than that. I believe that modern technological development, in conjunction with a market economy, has demeaned and diminished the great human faculty of taste. Bayley, Pile, Blake and Co. passively reflect in their theories a tragic corrosion brought about by current productive and social processes. Unlike them, I am not interested in rubber- stamping what is happening; rather, I am concerned about seeking ways of reversing these developments so that taste, with its sensuous and evaluative dimensions, can flourish once again.

But what sort of faculty is (or was) taste? In Keywords, Raymond Williams explains that ‘taste’ dates back to the thirteenth century, when it was used in an exclusively sensual sense - although the senses it embraced included those of touch and feeling, as well as those received through the mouth. Gradually, however, the associations of ‘taste’ with sense contracted until they became exclusively oral; while its metaphorical usages extended, at first to take in the whole field of human understanding. By the seventeenth century, taste had acquired its associations with aesthetic discrimination.

‘Taste’ was like having a new sense or faculty added to the human soul, as Lord Shaftesbury put it. For Edmund Burke, ‘what is called Taste ... is not a simple idea, but is partly made up of a perception of the primary pleasures of sense, of the secondary pleasures of the imagination, and of the reasoning faculty, concerning the various relations of these, and concerning the human passions, manners, and actions.’

Immanuel Kant, too, insisted again and again that true taste went far beyond the fancy to which Bayley, Pile and Blake would have us reduce it. Kant once argued that, as regards the pleasant, everyone is content that his judgment, based on private feeling, should be limited to his own person. The example he gives is that if a man says, ‘Canary wine is pleasant’, he can logically be corrected and reminded that he ought to say, ‘It is pleasant to me .’ And this, according to Kant, is the case not only as regards the taste of the tongue, the palate, and the throat, but for whatever is pleasant to anyone’s eyes and ears. Some people find the colour violet soft and lovely; others feel it washed out and dead; one man likes the tone of wind instruments; another that of strings. Kant argues that to try in such matters to reprove as incorrect another man’s judgment which is different from our own, as if such judgments could be logically opposed, ‘would be folly’. And so he insists, as regards the pleasant, ‘the fundamental proposition is valid: everyone has his own taste (the taste of sense).’ Thus, one might say, Bayley, Pile, Blake and Kant would all agree that it is a matter of no consequence if a man prefers lemon to orange squash, pork to beef, Brooke Bond to Lipton’s tea, or, I suppose, Golden Delicious to Cox’s.

But Kant immediately goes on to say that the case is quite different with the beautiful, as distinct from the pleasant. For Kant, it would be simply ‘laughable’ if a man who imagined anything to his own taste tried to justify himself by saying, ‘This object (the house we see, the coat that person wears, the concert we hear, the poem submitted to our judgment) is beautiful for me.''

Kant argues a man must not call a thing beautiful just because it pleases him. All sorts of things have charm and pleasantness, ‘and no one troubles himself at that’. But, claims Kant, if a man says that something or other is beautiful, ‘he supposes in others the same satisfaction; he judges not merely for himself, but for everyone, and speaks of beauty as if it were a property of things.’ Thus Kant concludes that in questions of the beautiful, we cannot say that each man has his own particular taste: ‘For this would be as much as to say that there is no taste whatever, i.e. no aesthetical judgment which can make a rightful claim upon everyone’s assent.’

Kant, of course, regarded such a position as simply a logical reductio ad absurdum-, but it is just this reductio ad absurdum which Bayley, Pile, Blake and Co. wish to serve up to us as the very latest thinking on taste. It does not even occur to them that there may be a category of the beautiful which seeks to make claims beyond those of the vagaries of personal fancy; for them, all ‘aesthetical judgments’ are not only subjective, but arbitrary. The only escape from such extreme relativism is Bayley’s last-minute appeal to the ‘objectivity’ of ‘principles of design’ rooted in talk about efficiency, practical function, technological sophistication and so on.

But my argument against Kant works in the opposite direction from theirs: for I believe that he conceded the relativity of even sensual taste much too quickly. For although tastes vary, it is not true to say that everyone has his or her own taste, in any absolute way, even in matters of sense. For human senses are rooted in biological being, and emerged out of biological functions; though variable, they are far from being infinitely so. Even at the level of sensuous experience, discriminative judgments about taste are not only possible, but commonplace. It is not just that we readily acknowledge one man has a better ear, or eye, than another. Judgments about sense experience imply an underlying consensus of qualitative assumptions. For example, a man who judged excrement to have a more pleasant smell than roses would, almost universally, be held to have an aberrant or perverse taste.

The problem is complicated, however, because this consensus is not simply ‘given’ to us: rather it can only be reached through culturally and socially determined habits, and these can obscure even more than they reveal. For example, we can easily imagine a society in which the odour of filth is widely preferred to the aroma of roses, and no doubt the social anthropologists can tell us of one. But what of individuals who prefer, say, rayon to silk; fibreglass to elm-wood; the dullness of paste to the lustre and brilliance of true diamonds; insipid white sliced bread to the best wholemeals; cheap and nasty Spanish plonk to vintage Chateau Margaux; factory-made Axminsters to hand-woven carpets; or tasteless Golden Delicious to Cox’s apples?

I am suggesting that modern productive, economic, and cultural systems, in the West, are conspiring to create a situation not so very different from that of our hypothetical example in which the odour of excrement was widely preferred to that of roses. In our society it may well be that a majority prefers, say, white, sliced, plimsoll bread to wholemeal. Bayley, Pile, Blake and Co. advocate uncritical collusion with this distortion and suppression of the full development of human sense and evaluative responses. But the judgment of true taste will inevitably be made ‘against the grain’, and equally inevitably run the risk of being condemned as elitist.

In aesthetically healthy societies a continuity between the responses of sense and fully aesthetic responses can be assumed. The rupturing of this continuity is, I believe, one of the most conspicuous symptoms of this crisis of taste in our time. This continuity still survives, of course, in numerous sub-cultural activities: for example in the sub-culture of fine wines. The production of these wines has only the remotest root in the function of quenching human thirst; they constitute the higher reaches of sensual response, where taste reigns supreme. In the connoisseurship of them, questions parallel to those Kant raised about true aesthetic response, as opposed to merely pleasant sensations, soon bubble towards the neck of the bottle. For, when he pronounces, the connoisseur certainly wants to say that such and such a wine is (or is not) good ‘for me’; but that is not all he wants to say.

Our connoisseur will certainly be prepared to admit his personal fancies, and even, perhaps, the idiosyncratic or sentimental tinges and flushes to his taste. He may well have a general preference for clarets rather than burgundies, and a particular liking for that distinctive, though hardly superb, wine he first drank on his wedding day. But, he will tell us, his fancies do not prevent him from discriminating between a bad claret and a good burgundy; nor from recognising that there are, in fact, better vintages of his wedding day wine than the one he personally prefers. When he makes statements of this kind, our connoisseur is acknowledging that he, too, is not merely judging for himself, but for everyone. He regards quality more as if it was a property of the wine itself rather than an arbitrary response of the taste buds.

Furthermore, he is aware that he exercises his taste in the context of an evolving tradition of the manufacture of and response to fine wines. Of course, this tradition is inflected by a plethora of local and regional preferences and prejudices; but such variations do not exclude the possibility of an authoritative consensus of evaluative responses. Indeed, most disputes between connoisseurs concern the fine tuning of the hierarchy of the vintage years. Connoisseurs assume that the tradition has arrived at judgments which are something more than individual whim or local prejudice. Anyone who consistently inverted the consensus, e.g. who regularly preferred vin ordinare to the supreme vintages of the greatest premier cru wines could safely be assumed to have a bad or aberrant taste in wines.

Even taste of the senses, therefore, can take us far beyond the arbitrariness of pleasant ‘for me’ responses; and as soon as we move into the various branches of craft manufacture, of, say, tapestry-making, furniture design, jewellery and pottery, we realise just how inadequate such responses are. For example, if a man said that a mass-produced Woolworth’s bowl, embellished with floral transfers, was as ‘good’ as a great Bernard Leach pot, I could not simply assent that he was entitled to his taste; rather I would assume that some sad occlusion of his aesthetic faculties had taken place. In the case of the fine arts, Bayley, Pile and Blake notwithstanding, it is quite impossible to evade the universalising claims of judgments of taste. It may be that there are those who believe David Wynne’s Boy on a Dolphin is a greater sculpture than Michelangelo’s last Pieta. But it is nothing better than vulgar philistinism to concede that this judgment is as good as any other, even if it happens to be a majority judgment.

The concept of taste then was an attempt to describe the way in which human affective, imaginative, symbolic, aesthetic and evaluative responses are rooted in, and emerge out of, data given to us through the senses. The idea of taste acknowledges the fact that, in our species, the senses are not simply a means of acquiring practical or immediately functional information for the purposes of survival. Nor is it just that we come to enjoy certain sensuous experiences for their own sake; the senses also enter into that terrain of imaginative transformation and evaluative response which seems unique to man.

Elsewhere, I have tried to explain this phenomenon, upon which the capacity for culture depends, in terms of the long period of dependency of the human infant upon the mother. For us, the senses play into a world of illusion and imaginative creation before they become a means of acquiring knowledge about the outside world. Even after he has come to accept the existence of an autonomous, external reality he did not create, man is compensated through his cultural life; there, at least, things can be imbued with value, and tasted through this faculty added to the human soul.

Predictably, the concept of taste only required conceptualisation and philosophical analysis at that moment in history when it became problematic. So long as men and women could ‘Taste and see how good the Lord is’, so long, in other words, as sensuous experience continued to flow uninterruptedly into cultural life, evaluative response and symbolic belief, the idea of taste (as something over and above sensuous experience) was simply redundant. It is not surprising, therefore, to discover that almost from the moment it was first used, ‘taste’ was already a concept fraught with difficulties.

The eighteenth century, for example, was preoccupied with the idea of ‘true’ educated taste, rooted in the recovery of the Golden Age of the classical past, as against popular taste - or the lack of it. The assumption was that this rift could be healed through education. But even before the end of the century, educated ‘Taste’ had acquired a capital ‘T’ and become suspect. Wordsworth and others railed against the reduction of taste to empty manners. In his history of Victorian Taste John Steegman argues that about 1830, taste ‘underwent a change more violent than any it had undergone for a hundred and fifty years previously.’ This change, he says, was not merely one of direction. ‘It lay rather in abandoning the signposts of authority for the fancies of the individual.’ Throughout the later nineteenth century, lone prophets like Ruskin, Eastlake and Morris denounced the decay of taste into ‘Taste’ or manners among the elite, and its general absence elsewhere in society. But they were bereft of authority. By the twentieth century, all the great critical voices had fallen silent. Even high aesthetic taste was widely assumed to be a ‘for me’ response. The thin relativism of Bayley, Pile and Blake became the order of the day. Commentators began to argue there was ‘no aesthetical judgment which can make a rightful claim upon everyone’s assent.’ Even a knowing middle class turned enthusiastically to Kitsch.

The causes of this destruction of taste are various and complex. The puncturing of the illusions of religious faith certainly made it harder and-harder to sustain belief in a continuity between the evidence of the senses and affective or evaluative response. Values came to be characterised as being ‘subjective’ and therefore, by implication, arbitrary; that area of experience which had once united them with physical and social reality began to disappear.

Mechanism began to replace organism, not only as the assumed model for all production and creativity, but as the paradigm for cultural activity itself. Modernism celebrated this elevation of the machine, decrying the ornamental and aesthetic aspects of work in favour of at least a look of standardisation and efficiency. The prevalent taste became the affirmation of those elements in contemporary productive life inimical to the development of taste; hence the attempt to identify the universals of taste with the principles of functional design.

Meanwhile, the growth of a market economy based on the principles of economic competition tended to lead to the triumph of exchange values over the judgments of taste. Indeed, the intensification of the market led to the eradication of many of the traditional and qualitative preconditions for the exercise of taste. The market in fact encourages the homogenisation of sensuous experience: it gives us Golden Delicious rather than more than two hundred local varieties. Simultaneously, however, through advertising and ideology, the market proclaims the value of choice. But a preference for Coke rather than Pepsi really has no qualitative significance; there can be no such thing as a connoisseur of cola. At the same time, political democratisation has somehow become co.nflated into a cultural rejection of any kind of discrimination or preference: taste has become bereft of authority and has sunk back into the solipsistic narcissisms of the subcultures, or the trivialising relativisms of individual fancy.

And yet, and yet. . . despite nerves and doubt about the status of taste, most of us still try to exercise it. And most of us demonstrate by our actions that we believe it to be something more than a ‘for me’ response. Indeed, proof against the assertions of Bayley, Pile, Blake and Co. is readily to be found in everyday life. Today, it is possible to question with relative impunity the politics, ethics, actions and even religious convictions of most of the men and women one encounters. There is widespread understanding that all such areas and issues offer legitimate scope for radical divergences and oppositions. No such generosity prevails over questions of taste. Rare indeed are the circumstances under which it is acceptable ‘decently’ to challenge an individual’s taste in, say, clothing, interior design, or works of art.

Indeed, I find that because, as an art critic, I offer preferential judgments of taste, by profession, I am exposed to intemperately energetic responses of a kind that simply do not arise in other areas of human discourse. Whatever these responses may or may not indicate about the nature of taste, they do not suggest that there is a general agreement that it is a ‘somewhat superficial matter’, of no greater significance than whether a man has black or brown hair, or prefers Scotch to gin.

Rather, this continuing agitation about taste suggests that it is a significant human responsive faculty, whose roots reach back into natural, rather than cultural or social history. But taste requires a facilitating cultural environment if it is to thrive — and it is denied this in a society which, as it were, chooses mechanism and competition, rather than organism and co-operation, as its models in productive life. Elsewhere, I have argued the case for the regulation of automated industrial production; and for restraint and control of such effects of market competition as advertising and market-orientated styling. I have suggested that, even in the absence of a religion, nature itself can provide that ‘shared symbolic order’ which allows for the restitution of a continuity between sense experience and affective life. But even such drastic (and improbable) developments as these would not, in themselves, be sufficient to ensure a widespread revival of the faculty of taste. For, if it is to emerge out of narcissism and individualism, taste requires rooting in a cultural tradition; taste cannot transmute itself into anything other than passing fashion if its conventions, however arbitrary in themselves, are lacking in authority. There is, of course, no possibility that the church, or the court, can ever again be guardians of more than sub-cultural tastes. The history of Modernism has demonstrated that it is folly to believe that the functioning of machines can provide a substitute for such lost authority. We therefore have no choice but to turn to the idea of new human agencies.

One of the most interesting texts in Bayley’s little book is a private memorandum by Sherban Cantacuzino, Secretary of the Royal Fine Art Commission, which deals with this possibility. Cantacuzino, too, cites Kant’s view that although aesthetic judgment is grounded in a feeling of pleasure personal to every individual, this pleasure aspires to be universally valid. Thus he seeks a greater authority for the Commission - an authority rooted in democratic representation, rather than public participation. ‘The Commission,’ he writes, ‘as a body passing aesthetic judgment, must feel compelled and also entitled to, as it were, legislate its pleasures for all rational beings.’

Many people understandably have a revulsion against any suggestion of social control in matters of taste or aesthetics; and yet the greatest achievements in this terrain, along with some of the worst, were effected under conditions where such controls applied. In our society, in their absence, the market and advancing technology, are having unmitigatedly detrimental effects on the aesthetic life of society. It is not the fact of institutional regulation, so much as its content, that should concern us: and I am arguing for an institution which, as it were, exercises a positive discrimination in favour of the aesthetic dimension. Unlike Cantacuzino, I do not believe this institution should necessarily be the Royal Fine Art Commission: rather, it might be some new agency, drawn from the Design, Crafts and Arts Councils, as well as from the Commission. But, unlike these bodies, it would have powers of direct patronage, and, as Cantacuzino puts it, ‘feel compelled and also entitled to . . . legislate its pleasures for all rational beings’. Indeed, I believe that such a rooting of taste in the authority of an effective institution of state would not be a limitation on aesthetic life so much as a sine qua non of its continued survival. For what is certain is that left to their own considerable devices, the development of technology and the expansion of the market will succeed in holding the faculty of taste in a state of limbo, if not in suppressing it altogether. But some kind of effective cultural conservationism, in the face of the philistinism even of ‘experts’ like Bayley, Pile and Blake, seems to me to be as much an obligation of good Government as the protection of our forests and national parks from the intrusions of technological development; or the provision of adequate educational and health facilities, free from distorting effects of market pressures.

1983