Peter Fuller's controversial views on Andy Warhol were at the root of his argument on aesthetics, now that the second draft of my screenplay about my father Modern Art is complete, I've decided it's time to start posting his most significant works. The below televised debate caused a huge stir when he was able to take on a room full of intellectuals on the subject of Warhol's work and what it means for the world.

Originally published in Modern Painters in 1989, this article details Peter's journey with Warhol's work and poses the question whether it's time we collectively make a decision.

Ivon or Andy: a Time for Decision

I've never been touched by a painting. I don't want to think. The world outside would be easier to live in if we were all machines . . . My work won't last anyway. I was using cheap paint.

Andy Warhol, quoted in Victor Bockris, Warhol p. 145

In one of his columns in The Nation, the New York critic, Arthur C. Danto, wrote that Andy Warhol was 'the nearest thing to a philosophical genius the history of art has produced'. I was surprised by this, not only because I found Warhol's art empty and banal, but also because I had read From AtoB & Back Again: The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. The most profound statement in this book is probably, 'Diet pills make you want to dust and flush things down the john'. Admittedly, Warhol himself once said to a reporter, 'I don't think many people are going to believe in my philosophy, because the other ones are better'. But I knew that Danto was himself a distinguished Professor of Philosophy. How could he have reached such a judgement? It seemed to me that only in a culture which had lost sight of the perennial concerns of philosophy with the nature of the good, the true and the beautiful - a dying culture - would a leading philosopher wish to celebrate Warhol as 'a philosophical genius'.

After expressing such misguided sentiments, I received a helpful letter from Professor Danto exuding bonhomie and camaraderie, but firmly putting me straight. He found my 'curmudgeonly thoughts' about Warhol 'a lot of fun'. After all, he has always enjoyed 'cranky, quirky writing' and he can see 'there is a good heart beneath it all'. My error, however - and here I can almost feel him patting my unphilosophical English head, just as he pats the snouts of his mad spaniels - lies in the fact that I 'look at [Warhol] the wrong way'. Ah! So there's the rub! 'In fact,' the good Professor continues, 'you are looking at him as though he were trying to do what Veronese did, only failing. Think of him instead as trying to do what Hegel did in the medium of commonplace objects, and you will get closer to the point.'

Portrait of Andy Warhol by Julian Schnabel

I fear that an awful lot of people are taken in by patronising pundits of this ilk. Since his death Warhol's reputation has risen exponentially. For months, book about Warhol succeeded book about Warhol with a serial monotony he would have admired. There was, of course, a monumental tome which accompanied the retrospective, in which celebrities vied with each other in the extravagance of their praise. 'There are the rocks, the sea, and the sky, the days, the hours, the minutes; pain; the temperature of a particular day - all permutations of reality - and there is Andy Warhol.' Who else, but Julian Schnabel.

As if that was not enough, there was also a massive monograph on the works by David Bourdon and sundry specialist catalogues and studies, especially on the formative years spent drawing fluffy show ads for I. Miller & Sons, Inc. Victor Bockris's biography, published early in 1989, was soon superseded by another, Loner At the Ball: The Life of Andy Warhol, by Fred Lawrence Guiles. As editor of an art magazine, I was all but submerged in a welter of Diaries, confessions and photographic essays, published not only by the great philosophical genius himself, but also by former members of his entourage, whether superstars or mere Factory drones.

I attended to the soul muzak piped out through these tomes of trivia and inanity, listening for just one indication that Warhol possessed intentions of the kind Danto attributes to him. I must admit that even if such a glint was forthcoming, it would have counted for little, for I had already stood in front of Warhol's works in his Museum of Modern Art retrospective, and had been underwhelmed.

'If you want to know all about Andy Warhol,' Warhol said, 'just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There's nothing behind it.' This may be one reason why the pictures are so numbingly boring. A sidewalk or a supermarket has more to offer the eye. The surface of these pictures reveals that Warhol's imagination was negligible, his painterly skills nugatory, and his aesthetic sensibility nonexistent. Hegel notwithstanding, there is nothing there except 'the evil of banality', anaesthesia itself. The real conundrum is why there are so many 'serious' people like Professor Danto, who are prepared to fritter away their time attending to such things; so many who seem willing to ignore the valiant endeavours of those who struggle to paint like Veronese - even if they often, or always, fail.

He loved to see other people dying. This was what the Factory was about: Andy was the Angel of Death's Apprentice as these people went through their shabby lives with drugs and weird sex and group sex and mass sex.

Andy looked and Andy as voyeur par excellence was the devil, because he got bored just looking. I remember reading a paper by a Freudian psychoanalyst who argued that if there was such a thing as 'libido' associated with Eros, or the Life Instincts, then, for the theory to stand up, there ought to be a hypothetical force, which he designated 'mortido', associated with Thanatos, or the Death Instincts. He suggested Narcissus as a prototype for a personality dominated by 'mortido'. Narcissus's infatuation with his own reflection in the still and silent waters of the pool was not so much a perversion of love as a manifestation of his longing for extinction. In love with himself, he was lost to 'the other'.

These days, I have less patience with Freudian psychoanalysis than I once had, least of all for those varieties of it which asssume the existence in all of us of a Death Instinct. And yet I must admit that consideration of the phenomenon of Andy Warhol has provoked in me a wellspring of sympathy for such ideas. For Warhol's self-absorption was such that he seemed barely able to connect with others, or the world. (The acquisition of my tape recorder,' he said, 'really finished whatever emotional life I might have had, but I was glad to see it go . . .1 think that once you see emotions from a certain angle you can never think of them as real again. That's what more or less has happened to me.')

Warhol's 'affectless' way of looking at objects in the world had nothing to do with any heightening of the powers of the senses, although there are those who still try to see him that way. For instance, Robert Rosenblum makes much of the fact that Warhol worshipped regularly at the church of St Vincent Ferrer at Sixty-sixth Street and Lexington Avenue. According to Rosenblum, Warhol himself created 'disturbing new equivalents for the depiction of the sacred in earlier religious art'. His galleries of myths and superstars, Rosenblum says, 'resemble an anthology of post-Christian saints, just as his renderings of Marilyn's disembodied lips or a single soup can become the icons of a new religion, recalling the fixed isolation of holy relics in an abstract space'. Rosenblum sees in Warhol references to 'the mute void and mystery of death', especially in the blankness of Blue Electric Chair, and even 'the supernatural glitter of celestial splendor' in an image of Marilyn Monroe which he relates to 'a Byzantine madonna'. There is, he feels, 'an impalpable twinkle of sainthood' in Warhol's portrait of Joseph Beuys. Warhol, Rosenblum concludes, 'not only managed to encompass in his art the most awesome panorama of the material world we all live in, but even gave us unexpected glimpses of our new forms of heaven and hell'.

But this is nonsense. Warhol offers only a superficial vision of the material world, and the 'glimpses' of heaven and hell are no more revealing than those we can derive from plastic madonnas and two-dollar religious trinkets. The emptiness in his work was never even an analogue for that contemplative emptiness and silence which mystics have long associated with the abnegation of the self and the enrichment of the soul. Rather, it reproduces the pornographic vacuity of a Jimmy Swaggart, or a Las Vegas Crematorium. Cheap nothingness, an oblivion of kitsch.

There is no indication in any of Warhol's painting that he ever glimpsed, say, the way in which the sun can touch the leaves of the trees and make them shimmer, or the glint in the wings of the dragon-fly as it hovers over the still waters of a pond. Warhol was too busy examining his own reflection. If he had been born in seventeenth-century Holland, when Vermeer was watching the way light modulated itself over the walls, Warhol would have been trying to use a camera obscura to photograph himself in the mirror.

Nothing reveals a painter's nature better than the way he paints flowers, and for Warhol, flowers meant painting by numbers. Apart from an Easter card for I. Miller & Sons, Inc., and an inconsequential floral cover for Vogue's Fashion Living in the early 1960s, Warhol's first painting of flowers was Do It Yourself (Flowers), 1962. This consists of an enlarged and partially completed version of a 'painting-by-numbers' image in synthetic polymer. Warhol then plunged into his frozen images of death and disaster, wanted men, electric chairs and crashed cars. Bockris says that it was Henry Geldzahler who suggested to Warhol that it was 'time for some life', and showed what he meant by pointing to a magazine centrefold of flowers. Soon after, the Factory began to mass-produce flower paintings of every size from miniature to mural [see plate 19b].

Altogether, Warhol's assistants seem to have produced more than 900 flower pieces. Sometimes, there were fifteen people working on them at once. The images were reproduced on canvas by a photo-silkscreen technique. Unlike many of Warhol's pictures, these were not straightforward photographic reproductions. The contours of the flowers were touched up by hand, though rarely Warhol's own. Whatever the size or shape of the canvases, they were mounted onto standard-size stretchers provided by a local art materials shop, so the image is often cropped in peculiar ways or surrounded by a wide, white border.

In 1965, when Warhol held his first exhibition in France, he decided that he would show only flower pictures. 'I thought the French would probably like flowers because of Renoir and so on,' he said. They're in fashion this year. They look like a cheap awning. They're terrific.'

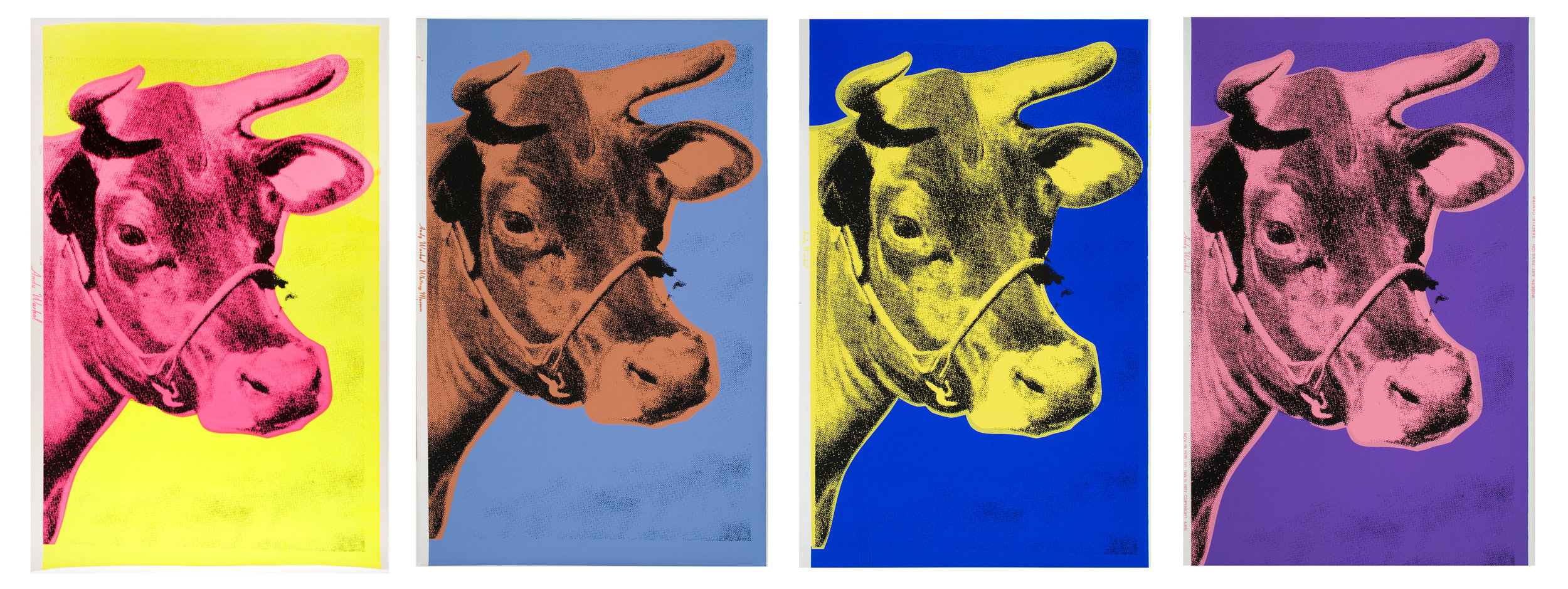

These synthetic flowers were as close as Warhol ever got to the idea of using his senses to attend to natural forms. Even so, any such allusions to nature as they may contain are purely coincidental. According to Rainer Crone, Warhol found the image in a women's magazine where it had won second prize in a housewives' photography contest. (The housewife in question later tried to sue and was paid-off by Warhol with two flower paintings, which she immediately sold through Leo Castelli, Warhol's dealer.) Crone says that, together with Cow Wallpaper and the Silver Clouds, the Flowers were unique 'by virtue of their meaningless image content'. But, he claims, the pictures were not entirely 'dehumanised' because 'their banal abstract form' was 'a gauge against which to measure Warhol's other work'. Warhol had created the form of the flowers solely as a means to carry colour which, in these works, he used 'strictly decora- tively'.

Warhol's 'decoration', however, had nothing to do with aesthetic enhancement, nor yet with any longing for rarefied beauty and pleasure. Instead, he was interested in a sort of negative corollary of the decorative, a despoliation which bored and numbed. According to Peter Gidal, another Warhol hagiographer, this self-conscious cheapening of the image is what matters and makes Warhol's works worthy of attention. 'One accepts the flower pictures,' he writes, 'within one's taste even though beforehand one had the fine-art sense to dislike their cheapness . . . It's as if Warhol had managed to make "city flowers" out of real flowers, and that is part of his aesthetic; broadening the range of acceptability.'

There were also those who heralded the flowers as 'the ozone of the future'. Small wonder that the more perceptive critics, when confronted with these works, have scented there the stench of the mortuary and of extinction. Much has been made of the fact that the flowers are poppies - though not, as Bockris points out, opium poppies. And yet death is present not so much in the imagery itself as in the way the flower paintings were made. They secrete the vile odour of 'mortido' unredeemed by any aesthetic consolation. As even one of Warhol's most sycophantic admirers, Carter Ratcliff, has put it, 'No matter how much one wishes these flowers to remain beautiful they perish under one's gaze, as if haunted by death.'

Now let us turn to the painting, Flower Group [see plate 10a], which Ivon Hitchens painted in 1943 - a picture which vibrates with light and life. It reminded me of that moment in 1858, when John Ruskin came to terms with the gorgeousness of the great Venetian painters, especially Veronese, and recognised 'a great worldly harmony running through all they did'. For a time, Ruskin came to believe that this 'worldly harmony' had more spiritual content than most religious painting.

In one sense, Hitchens's chosen subject matter was banal enough: a vase of flowers, including poppies, placed in an interior. His way of seeing, too, was unembellished. Patrick Heron once described him as engaged in 'the humble transcription, in terms of paint, of sensation itself'. As Heron points out, he eschewed the self-consciously 'symbolic' and 'poetic', even though these were much in vogue among his contempories. And yet, in pictures like Flower Group, the motif is not only fresh, but also transfigured -just as Van Gogh could transfigure a pair of boots and imbue them with the tragic sentiments of a pieta.

This transfiguration is not some kitsch 'added extra' like Warhol's sprayed glitter around the head of Beuys, rather it springs directly from Hitchens's consummate visual intelligence. 'A picture,' he said, 'is compounded of three parts - one part artist, one part nature, one part the work itself. All three should sing together.' He looked with longing - love is not an inappropriate word - on the visible world, and he searched hard until he had found pictorial equivalents for what he saw, and, indeed, what he felt about what he saw. He tried to realise his truth to nature through composition rather than through imitation of the immediate appearances of things. He abandoned the focused perspective that had dominated Western landscape painting, and turned rather to a way of depicting which drew on his knowledge of Japanese pictorial composition, on Cubist space and on Fauvist colour. But, for Hitchens, all these things helped to provide him with the plastic and pictorial means through which he could express, with a striking freshness, an ancient yearning for a sense of unity with the world of nature. 'Art,' he used to insist, 'is not reporting. It is memory.'

The image of the landscape as paradise is always derived, in some sense, from memories of fusion with the mother. This, I think, may have been what Roger Fry was referring to when he talked about the dependence of the purest aesthetic emotion upon the arousal of 'some very deep, very vague, and immensely generalized reminiscences'. It was little short of a tragedy that all of Hitchens's paintings of the female nude were excluded from his 1989 retrospective at the Serpentine Gallery, for Hitchens's pictures of reclining women were deliciously free of those injured imagos of the fallen human body which haunt the paintings of the School of London today. Somehow, his fresh pictorial techniques allowed him to infuse the familiar symbolism of woman-as-landscape with a new life, in much the same way that Henry Moore's new sculptural forms enabled him to effect something similar in sculpture.

For Hitchens, as for so many of the great English landscape painters, landscape was more than the locus for sense experiences, more than a matter of topography. In those glimpses of paradise which he offers - especially in the marvellous series of paintings of a rather pedestrian view of Terwick Mill, which quite rightly formed the core of the Serpentine exhibition - formal means have replaced the relics of religious iconography and the tired devices of picturesque pastoral poetry. The intimations of unity and transcendence in Hitchens's paintings are achieved through formal means. While not, perhaps, 'the ozone of the future', his pictures remain uncompromisingly secular and modern. Yet in another sense, they retain a strong if silent feeling of continuity with the aesthetic and spiritual truths of the past. As a painter of the common-or-garden, he is, one might say, on the side of the angels, or at least of life.

There are no doubt those who will say it is wrong to compare two artists whose work is so different in intention, but in a way, that comparison has already been made. 'At present,' writes Lynne Cooke, my weather-vane of art-institutional orthodoxy, 'there seems to be a widespread consensus that the recent artists who require most study are Warhol and Beuys.' It is this consensus among the historians and art administrators which dictates that Warhol should have a major exhibition at the Hayward Gallery while Hitchens received only a half-hearted showing, apres Warhol's juvenilia, at the Serpentine. (Warhol, it should be said, last received a full-scale retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1971; Hitchens has not had a major institutional retrospective since his Tate Gallery showing in 1963. I discount the small exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1979, like that at the Serpentine in 1989, as rather half-hearted affairs. Needless to say, Hitchens's work is practically unknown in the United States.)

A few years ago I tried to interest the major London art institutions, especially the Hayward Gallery, in a show about British landscape painting from the 1940s until the present day. My idea was to begin with the paintings of Hitchens, Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, Victor Pasmore and others, from the war years, and to reveal how, contrary to the teaching of the 'consensus', the English landscape painting tradition had flourished right down to the present day. To take just two examples from among many, I would have included paintings by William Tillyer and Derek Hyatt, two of the best living painters of the landscape. This was a project which I knew would have broken new ground, and I remain convinced it would also have been popular with British gallery-goers, who have always responded enthusiastically to English landscape.

There was, however, no interest among the institutions. Joanna Drew, director of the Hayward Gallery, has since found space in her programme not only for the Warhol retrospective, but for one by Gilbert and George. Drew told me that she would only give consideration to a landscape exhibition which contained work by Conceptualists, photographers and others using 'new media' - that is, the sort of landscape show which would have had no aesthetic value and would have been almost as successful in keeping the public away as the Hayward's recent exhibition of minor Latin American genre art. Landscape painting, as such, she told me, was a 'funny business' largely pursued by amateurs. Warhol, incidentally, could certainly not be accused of 'amateurism'. 'Business art,' he said, 'is the step that comes after Art. I started as a commercial artist, and I want to finish as a business artist.' And so he did.

On the other hand, what Ivon Hitchens had to say could only have been achieved through painting of the purest and most disinterested kind. In one sense Hitchens was a consummate professional, in another he was sustained by the conventions of amateurism - certainly by its obliviousness to fame and fashion. The same, I believe, is also true of many of the best landscape painters who have come after. Perhaps they don't paint as well as Veronese did; nevertheless, such work is more worthy of our attention and study, and, more importantly, more conducive to our enjoyment, than Warhol's ersatz petals of death or Beuys's deceased hares. And that would be true even if Warhol and Beuys were the greatest philosophical minds the history of Western art has yet produced.

1989