A version of this article appears in the April 2015 issue of Modern Painters.

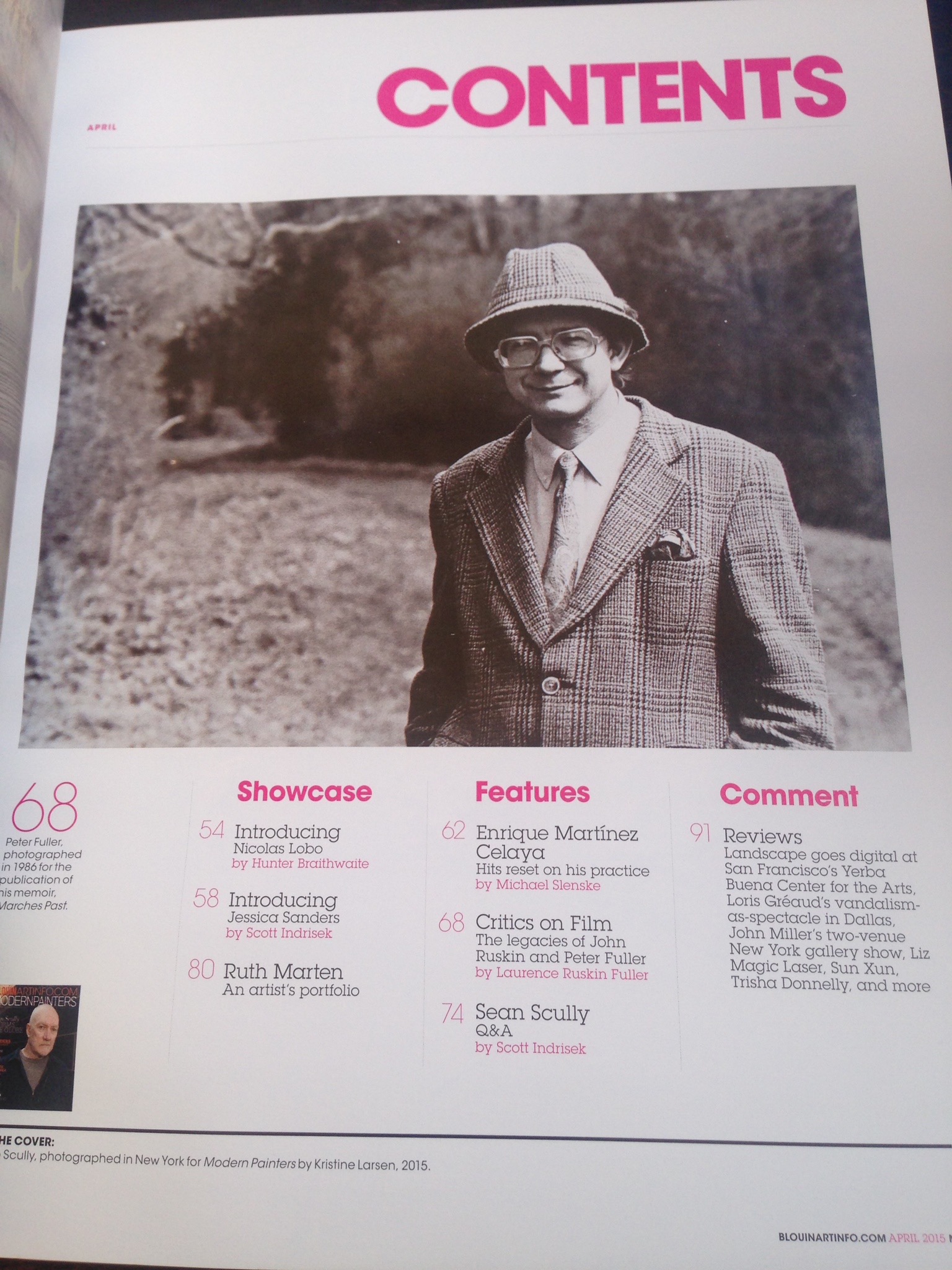

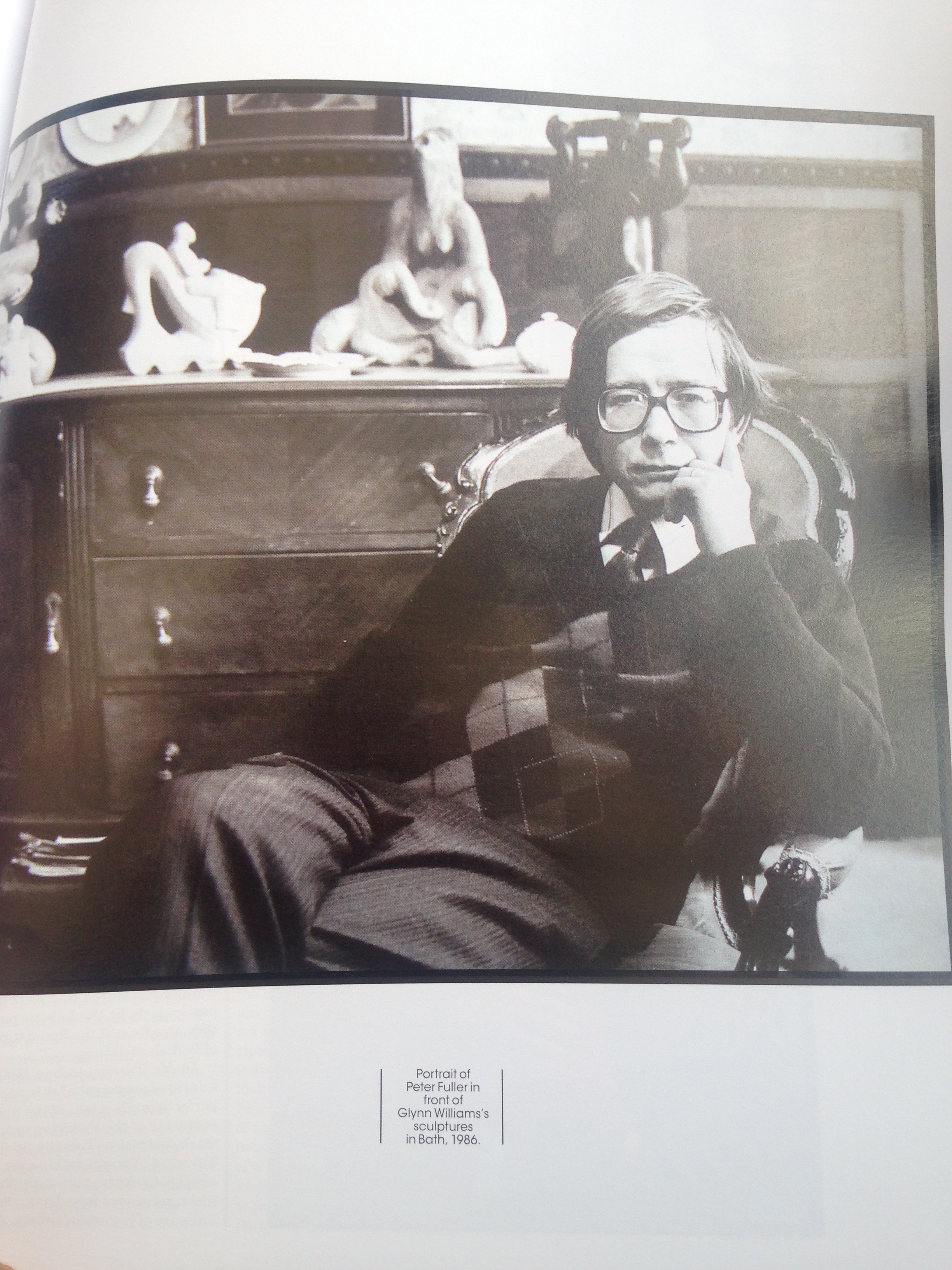

Peter Fuller reading the first issue of Modern Painters, the magazine he founded in 1986

by Anthony Daly

Peter Fuller was like a punch in the guts to the art world from 1969 to 1990, and until his last breath he was a radical. His writings spanned art history, psychology, sociology, aesthetics, biology, and religion, all emanating from his primary fascination with the arts. His ideas were ahead of their time, punctuated throughout with a belief that cultural reformation was possible through art. In this sense he was a radical-conservatist. In his later years, he was heavily influenced by the works of John Ruskin, and in 1987 he founded this magazine, naming it after the series of books by Ruskin entitled Modern Painters. Not only did Fuller emulate the man in naming his magazine, but he named me, his only surviving son, Laurence Ruskin Fuller. My own journey has taken me to Los Angeles, where I live as an actor and filmmaker. Recently, I’ve found myself deep in research for my next project, a screenplay about my father (I like to think of it as the Raging Bull of the art world).

Investigating my father’s radicalism 25 years after his passing, I find many connections to my own penchant for filmmaking, and to the field at large. Some might think the position of art philosopher is a conservative one to take in society. In this case I would like to reveal its antithesis. Although it is conservative to uphold values of the past, it is radical to use such values in the present to bring about change through cultural revolution.

Fuller peeled back the layers of cash that surround much contemporary art. In doing so he raised his pen with particular sting toward the works of Andy Warhol, Julian Schnabel, and Conceptual art in general. Then, through psychoanalysis, he turned inward, revealing his difficult and unresolved relationship with his evangelical Baptist father as the causeof his intense intellectual pursuits and ultimately his turbulent struggle in search of secular spiritual experience. As a result, he sought consolation in the transcendent potential of art, in particular that art which reflected a reimagining of the external world. He recognized a powerful sense of spirituality in man’s connection to nature in the works of Arthur Boyd, Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossof, John Bellany, Cecil Collins, and especially in the sculptures of Henry Moore. This secular sense of spirituality through a connection with the natural world is often considered fundamental to our nature, recurring throughout art history. In Victorian England, it emerged in the texts of John Ruskin, and it was through Ruskin’s conception of how spirituality can be integrated into Western culture that Fuller chose to express his own view on modernist values in his seminal works Modern Painters, Images of God and Theoria. With two 2014 depictions of Ruskin out in mainstream cinema, I would like to take a look at how this unconventional literary radical is being remembered through the camera lens.

Greg Wise as John Ruskin in Effie Gray

Mr. Turner and Effie Gray both feature the character of John Ruskin prominently. Both films rightly depict him as a Victorian social and cultural commentator, with prolific writings on art, architecture, and sociology. Yet little is said about the prophetic undercurrent throughout his writing that industrial capitalism would fail us and that the solution to this failure could be found in nature and the arts.

In this sense, he, like Fuller, was a radical-conservatist. A number of Ruskin’s ideas were implemented in government policy, particularly by the Labour party, and they also formed the foundations of British socialism. In Mr. Turner, Joshua McGuire’s hilarious portrayal of this eccentric figure perfectly nails much of the pompous posturing of the Victorian era. Standing in stark contrast to Timothy Spall’s J.M.W. Turner, a straight-talking yet emotionally complex Cockney gentleman, Ruskin looks like a ridiculous fop who is completely unaware of his own wankery. As Ruskin’s relationship with Turner is not the central focus of the piece, McGuire and director Mike Leigh get away with this somewhat superficial depiction in the name of fun. However, in reality, it would be false to deny the importance of Ruskin’s writings to the sustained legacy of Turner, starting with a series of essays he initially wrote in defense of the artist, entitled Modern Painters. In 1985, Peter Fuller wrote about their relationship in Images of God: “The first, and in some ways, the greatest cultural obsession of Ruskin’s life was with Turner. Indeed, he set out to write his first major work, Modern Painters, as a defense of Turner against callous contemporary reviewers. The book swelled into five volumes. In the first of these, Ruskin argued that Turner was more ‘realist’ than any landscape painter of the past, or the present, not just because he had more accurately observed the formation of leaves, branches, and mountain structure, than they but because he had also revealed nature as the literal handiwork of God.” He continues, “Ruskin’s ‘reading’ of Turner makes sense if one sees the element in art which goes beyond verisimilitude not as revelation of God so much as the artist’s own expression of imaginative transformation.”

Still from Mr. Turner

Had they elaborated on Ruskin’s influence on Turner’s career, the filmmakers no doubt would have included a very cinematic event in which Ruskin burns any and all of Turner’s paintings that hold sexual content — Ruskin admitted to and even bragged about this “bonfire.” Although the validity of this claim has been contested, it nevertheless stands as a telling symbol of both Ruskin’s relationship with Turner and his own troubled psyche. Fuller writes of the event in Theoria (a modern reevaluation of Ruskin’s writing published in 1988): “[Ruskin] also plunged into the arrangement of the vast number of unclassified drawings Turner had left behind athis death. Though he saved many drawings which would otherwise have gone rotten in the cellars of the National Gallery, he did not hesitate to destroy others he deemed too sensual. This destructive behavior seems to have been a perverse defense against a threatening aspect of himself.”

Still from Effie Gray

Which brings us to the film Effie Gray. Dakota Fanning is unrecognizable in the role of Effie, easily one of the most convincing depictions of a Brit — let alone a Victorian one — by an American so far on film. Greg Wise, playing Ruskin, gives a sympathetic and sensitive portrayal of this complex figure. Yet he is unable to save the film from its central theme: that the man was a big meanie who will be remembered for not having sex with his wife. Fuller writes of their difficult marriage in Theoria: “The early days of the marriage were peaceful enough, as if by marrying Effie he had ‘solved’ the emotional turbulence which constantly threatened him.” However, “beneath the surface, the marriage was hollow. Neither partner was really capable of relating to the other, emotionally, intellectually, or sexually.”

The latter observation takes the central focus of the narrative in Effie Gray, portraying the woman as the victim of her sexually repressed Victorian husband. The difficulty with this film comes not from its execution (the filmmakers did an excellent job on all levels of production, and it deserves to be seen) but from its fundamental reason for being. I in no way condone Ruskin’s unaffectionate behavior toward Effie Gray, nor do I think his unorthodox sexual habits should be left out of any in-depth account of the man. However, by condemning Ruskin for this indiscretion instead of taking a deeper look into the causes of this behavior, the film overlooks one of the greatest minds of the Victorian age, reducing his legacy to being sexually repressed and a bit of a bully (unlike all the other British Victorians). This position on Ruskinis not unpopular, Fuller explains in Images of God: “In the middle of the 20th century, practically nothing was left of Ruskin’s once towering reputation except a malicious interest in the story of his private life.”

While the film and the book Effie Gray are put forward as socially progressive documents, I would think it even more socially progressive, if we’re looking at Ruskin’s sexual inadequacy, to relate his failings as a man directly to his successes as a writer — that his inability to relate to people, perhaps spawning from intense insecurity, transferred these natural feelings of love and spirituality to nature, architecture, society, art, and writing. The results of this transference gave birth to some of the best ideas of the Victorian age, whose legacy is evident in the pages of the magazine you’re now reading, and were the product of a man whose ideas as the first ecologist we may now turn to in the smog clouds of the 21st century. A greater story lies just beneath the surface.

In Memories of the Future, a documentary about Ruskin that Fuller made in 1984 with longtime collaborator Mike Dibb (the director of Ways of Seeing), Fuller argued that the repression of Ruskin’s interpersonal relations redirected this energy into a meaningful interaction with the surfaces of the natural world, something perhaps akin to the feelings of love we might experience with our partner. This experience reflected visually, emanating from a canvas by Turner, for instance, reinstating the perspective that there was a world outside the social realm that could generate feelings of intense pleasure. Bound up in religious morality, this ideology became a refined outlook on human culture. In Theoria, Fuller writes, “Ruskin’s correlation of the substance of the earth with women’s bodies is vivid and sensuous. It vibrates with the intensity of the sexual experiences he never knew; the joy he experienced when he came near mountains was ‘no more explicable or definable than the experience of love itself.’ ” The deeply flawed figure of Ruskin can provide us some answers, not by example of his own life, but in his messageof hope through the salvation of human culture and our relationship to nature.

From the 1980s on, Peter Fuller was lauded, by himself as much as others, as the successor to Ruskin. However, this was the source of much contention within the art world at the time. Julian Stallabrass writes in The Success and Failure of Peter Fuller, “Ruskin was a restless, comprehensive intellectual and a fine prose stylist, he was moralistic, a purveyor of elevated journalism, ill at ease with his epoch and his sexuality, and somewhat mad; all these qualities suited him inthe role of Fuller’s alter-ego.”

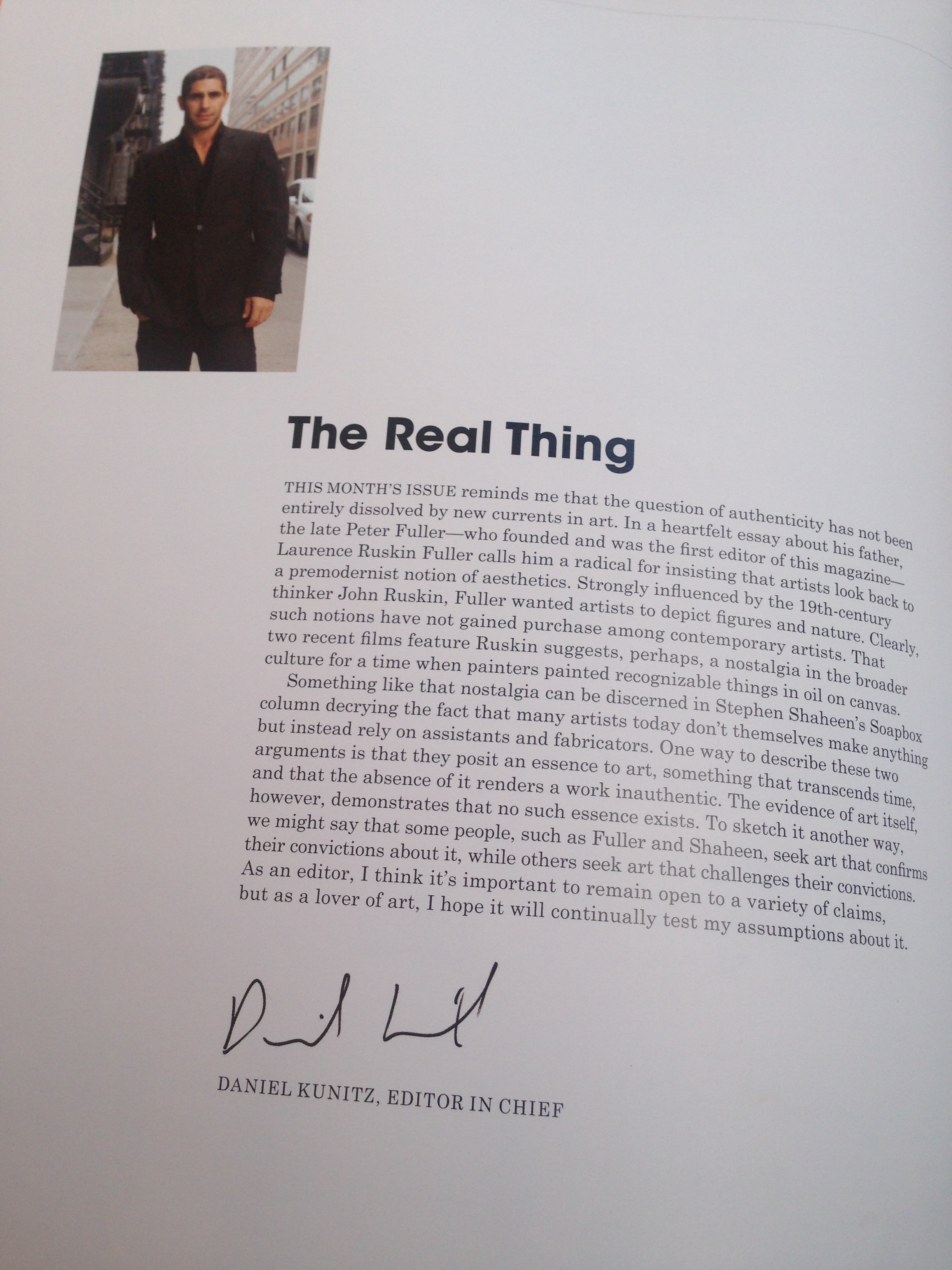

Stephanie Burns, Peter Fuller & Laurence Ruskin Fuller

Because of his intensity, my father had many adversaries. I was three years old when he died suddenly in a car accident in 1990. The incident rocked the art world, and I grew up in the shadow of an absent genius. Until undertaking this project to bring him to life on film, I had no idea who my father really was; understandably, much was kept from me as a boy, and consequently much is being revealed to me as a man. I recently came upon a box in the cupboard that my mother gave to me, which I think she was keeping from me until I was mature enough to deal with it. It was full to the brim with snippets of obituaries and letters of condolence that had flooded in from artists, philosophers, art dealers, writers, influential political figures, all the way to the Prince of Wales, as well as, of course, fellow critics like Clement Greenberg, whose obituary of Fuller was published in Modern Painters Volume 3 Number 2: “The light that Peter Fuller brought was more like lightning than day or lamp light. And more like heat lightning than any other kind; it didn’t always strike a ground object. And it could be fuliginous too, which is incompatible with any kind of lightning. Yet it illuminated.”

Yet in the years following his death, Fuller became a bad word at many dinner tables in England. In 1999, The Guardian published an article about him, “This Man Made Britart What It Is. He Would Have Hated It.” Wrote Jonathan Jones, “Fellow critics and art world luminaries queued up to deliver tributes at the time, but many must have had their fingers crossed: Fuller was widely loathed. But no one doubted that this man, who founded a successful art magazine and wrote a series of provocative books, would be remembered as a great critic.”

To get to the bottom of why my father was so controversial, we need to understand the conditions that brought him into prominence, beginning on March 17, 1968. A swelling mob of disenfranchised students was gatheringin Trafalgar Square, protesting the warin Vietnam, and afterward, 8,000 protesters marched on to Grosvenor Square, where Vanessa Redgrave delivered a letter of protest, and a battle with the police ensued. Soon after, a key figure at the center of this movement, Tariq Ali, formed the newspaper Black Dwarf, for which Fuller wrote under a pseudonym. There was a huge swell of cultural change. Art galleries were popping upall over London, the city housed a powerful young community of artists and intellectuals, and Fuller was a central force. Through writing for Black Dwarf, he was introduced to John Berger. Over the course of many discussions andlively debates with Berger, both public and private, Fuller recognized art’s transformational potential. Fuller became one of Marxist aesthetics’ strongest voices, held up as the successor to Berger. He wrote for such publications as New Society, New Left Review, and Seven Days, and authored such books as Beyond the Crisis in Art, The Naked Artist, and Art and Psychoanalysis, in the acknowledgments of which he writes, “[Berger] more than any man taught me how to write about art.”

In his memoir, Marches Past, Fuller recounts how Berger said to him during this time, “Strange how we work and walk, the two of us. Sometimes it seems to me that we are each a single leg of some other being who is striding out.” However, as the early 1980s came around, Fuller began to talk and write more about Ruskin as a way to combat the anti-aesthetic values of modernism, and in 1984, Berger and Fuller fell out over this shift in taste. After a lengthy and uncomfortable phone call, Berger said that turning to Ruskin was “a betrayal of Marxism,” after which the two never spoke again, and Fuller was perceived as moving to the right. In 1988 Fuller published Seeing Through Berger, a brutal account of his falling-out with the Marxist philosopher: “The really radical artistsof our time may yet turn out to have been those who . . . endeavored to pursue the good, the true, and the beautiful in such unpropitious times,” he wrote.

Central to the differences between the two men was that Berger wished to unravel the “catalogue of private property,” as told through conventional art history, and the misuse of art for the purposes of power and dominance throughout Western culture. While Fuller acknowledged this perspective, and in fact was greatly influenced by it, he was unable to accept it as a full account of the human experience in the creation of or engagement with a work of art. For instance, within each art movement there is a normative tradition; however, every so often a genius like Picasso comes around and throws ideology out the window. Both men saw that Ways of Seeing had not accounted for a masterwork; explorations there in were vehement. Fuller sought the sublime realms of spirituality and saw that, before him, Ruskin had explored this phenomenon in his assessment of Turner’s work, initially attributing it to recognition of the handiwork of God. Yet both Fuller and Ruskin were atheists (Ruskin turned away from God later in life, whereas Fuller was a teenager when he began to rebel against his Evangelical Baptist father). And so Fuller began a secular pilgrimage to replace the shared symbolic order once held up by religion, now taking refuge in art, in particular the ecological and spiritual symbolism made possible by the reimagining of the external world. With a painting by Lucian Freud on the front cover of its first issue, Modern Painters magazine was born not out of political interest, nor religious, but as an exploration of the aesthetic dimensions of life. At the end of one editorial Fuller wrote, “Modern Painters, however, will continue as it began. We will defend aesthetic values against all those who threaten them — whether from the left or the right, or both.”

With Berger on his left shoulder and Ruskin on his right, he marched forward, roaring toward a “Fuller Theory of Art.” April 28 marks 25 years since the car crash that claimed my father’s life and left a gash in the canvas of his generation. Looking back at the man who came before me, in the philosophy of Fuller, I see the light he cast for us in the darkness of the post–cyber revolution. Progress insulated within society can take us so far, but it can never come close to compensating for the immense value of the authentic human experience of the world around us. As sophisticated as Western culture has become, conquest over nature only leads to our own destruction, aswe are of nature. Thus placing value on the human spirit, skilled expressions of sentience in our advancing mediums are the most subversive acts of all.